Depending on when you read this, “C&O” may not signify any meaning whatever. Here it is: C&O designates the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, one of America’s great railways which originally ran from Cincinnati to Norfolk. And West Virginia was squarely in its pathway — the C&O entered the state (from Ohio) close to Huntington, then through the Kanawha Valley — Charleston, etc., and eastward up the Kanawha and New Rivers, then following the Greenbrier and tunneling through a mountain eastward into Virginia. There is a concrete marker just east of Alderson, on the Greenbrier River, marking the halfway point between Cincinnati and Norfolk.

I’ll state my disclaimer here: I am not, nor have I ever been, really knowledgeable about railroads. That is a huge subject unto itself, embodying many chapters in our nation’s history. The science, math, engineering, politics, geography, societal and economic impact of railroads in America compose a huge slice of who we are as a nation, and the story will continue to build upon itself. But I feel a special personal kinship with the C&O Railroad, and so I’ll share a few personal experiences.

The South Charleston Railroad Yard was a busy place, and a source of constant interest to me, a four-year-old boy caught up in the view of the railroad yard from the front window of our little house on Franklin Terrace. Cars: coal cars — “hoppers,”- flat cars, boxcars, and tank cars — were moved from track to track, pulled or pushed by small locomotives designed for that specific purpose. Those small engines were known as “dinkies.” In fact, our next door neighbor on Franklin Terrace, Mr. Midkiff, was a dinky engineer. It was an operation to watch, putting cars together to “make up” a train for its destination. Later, as a youngster I spent time on and around the railroad, walking the cross ties to school, hanging around the South Charleston freight yard where coal, chemicals and other natural products were loaded, unloaded and/or shifted to other cars as part of the around-the-clock operation of a busy train yard.

My first on-train experience was a trip from Charleston to Alderson to visit my grandparents. Dad put Alice and me on the train, talked with the conductor about our destination. The conductor put a tag on a string around each of our necks, sat us side by side, and off we went. I remember absolutely nothing about three-hour the ride itself, just arriving at the Alderson station where we were greeted by Granddad Farley.

To take that trip alone was a big deal for us; we were six. In the mid-1930s train travel was very, very safe, and it was not uncommon for kids, looked after by conductors and porters, to ride alone on passenger trains. But still, I’m sure Alice and I rolled our eyes at each other more than once. A couple of years later I rode that same train to Alderson with Paul, Dad’s brother.

My only memory of that trip was that the conductor gave me a small glass container in the shape of a train and full of candy. Those containers, which were made in many shapes: Santas, telephones, airplanes, etc., have been collectors’ items for many years.

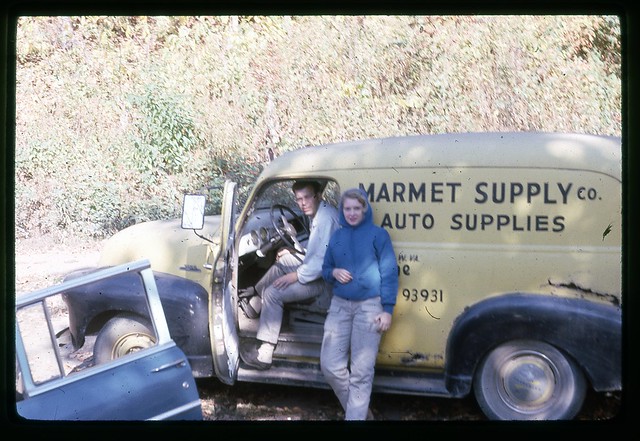

At some point, after we had moved from Franklin Terrace to Sycamore Street, I think at about age ten, I started to walk to the South Charleston “yard” and watch the action. The yard workers had a very small shack between sets of tracks, out of which they would carry out their various tasks. One day, I carefully walked across the tracks to the work shack, with a workman waving me to go back out of the yard. I just kept going till I got to where he was standing. Kindly but gruffly, he took me into that magic place and gave me a direct lecture about the dangers of the yard, and what to watch for when walking the tracks. Well, that started it. From there I made friends with two or three other workers, and they would watch out for me as I made my way to the shack — my shack now; my personal castle. I graduated from that special time after one summer’s reign. But I learned about noise, and the smell of steam, and the clanging of cars banging against each other, the cinders and coal dust, and the unique sound of steam emitting from the boiler. Of course, I didn’t really learn about those things — I just got the sense of them.

During the seventh and eighth grades, a group of us — all boys — walked the cross ties to school two or three times a week — about a mile. Sometimes, when we would hear an oncoming train, someone would put a penny on the track and the train would flatten it into a shining disc. If you could find it among the limestone rocks that formed the track’s ballast, you could give it to the girl of your dreams as a special trinket. If we had a newcomer with us on a really cold day, we’d try talk him into putting his tongue on the track. How dumb. But one guy named Dewey did, and his tongue momentarily stuck to the track — at which we howled. Such were the types of entertainment in those days.

Our house on Sycamore street was about a quarter mile from the railroad, so the sound of steam whistles pierced the night air on regular schedules, and in summertime, with the bedroom window open, those passing trains gave me a sense of pleasure and comfort. Many nights, reading by flashlight, the late train would be my signal to put the Zane Grey book away and go to sleep.

I won’t go into it here — read the section called “Sleeping Out,” and you’ll get the story of how we would watch the Fast Flying Virginian go by at 5:30 in the morning.

One of my favorite railroad memories.

So that’s how it started for me with the C&O. There were other train trips later in my life, but it was the early fascination that got me going. And that was soon to be reinforced when I introduced myself to country music on our radio. Living in West Virginia, there were many country music broadcasts on our AM radio (at that time FM didn’t exist), and I found them all. Of course, the Grand Ole Opry, broadcast on Saturday nights, was the king of them all. And train songs were immensely popular. I was about twelve when this phase began, and songs like “The Wreck of The Old 97,” “Wabash Cannonball,” “Freight Train Blues,” and “Streamline Cannonball” were featured weekly, which continued to whet my appetite for train music. You’ll note references to my own train songs elsewhere in these short pieces, and somewhere, perhaps in the family “archives,” there is a recording of them, written and performed by yours truly.

It naturally followed that when I began camping on New River and elsewhere, the freight trains — hauling coal, mostly — kept our gang company. Since sound travels so well across water, especially at night, we could hear an approaching train from a great distance, and the great steel wheels clacking on the track could be heard long after the train was out of sight. Daytime trains were also special, because you could hear them coming, see the smoke and then come into vision. Usually, if I was standing in knee-deep water with fishing rod in hand, I’d just reel in and watch, and listen.

Waterways made natural locations for railroads, for they cut through mountains and typically would provide for a good grade or slope. So as I camped on many streams over the years, it was common to find a railroad following the waterway, usually across the river from camp. Made for good fishing. Or if the fish weren’t hitting, didn’t matter. Either way, I win.

Others: Granddad Hale, Don Hale, Pat Hale, Dave Farley, Kenny Pulliam, Lloyd Parsell, and many others shared that feeling for the railroads and trains. After Granddad died in 1966, there were just a few of us who were loyal to the steam locomotive, steam whistle, and all that, because it was all replaced by diesel engines beginning in the early ‘sixties. With that went the steam whistle, the other noises and odors and eccentricities of the steam locomotive. And none of us liked it — at all. Call us reactionary, we don’t care.

The greatest of the train song writers was the immortal Jimmie Rogers. The Singing Brakeman. Read about him. Briefly, he was a Mississippi guy who, in his mid-twenties, was working on the railroads. Played guitar. Began writing and recording many songs, among them his famous train songs. He really captured the romance of the railroad, and though his career lasted only six years, his train songs survive to this day. Check it out . . . you’ll get a true impression of what it was like in the 1920s and 30s, with hobos, the Depression, life in the south. Wonderful stuff. His “Waiting for A Train” hit the charts in the early thirties, and he was an overnight star. Of course, his railroads were in the south, so you won’t find the C&O mentioned in his lyrics. But the stuff of trains is there, so soak it up. Jimmie Rogers died of tuberculosis in 1932.

A couple of notes:

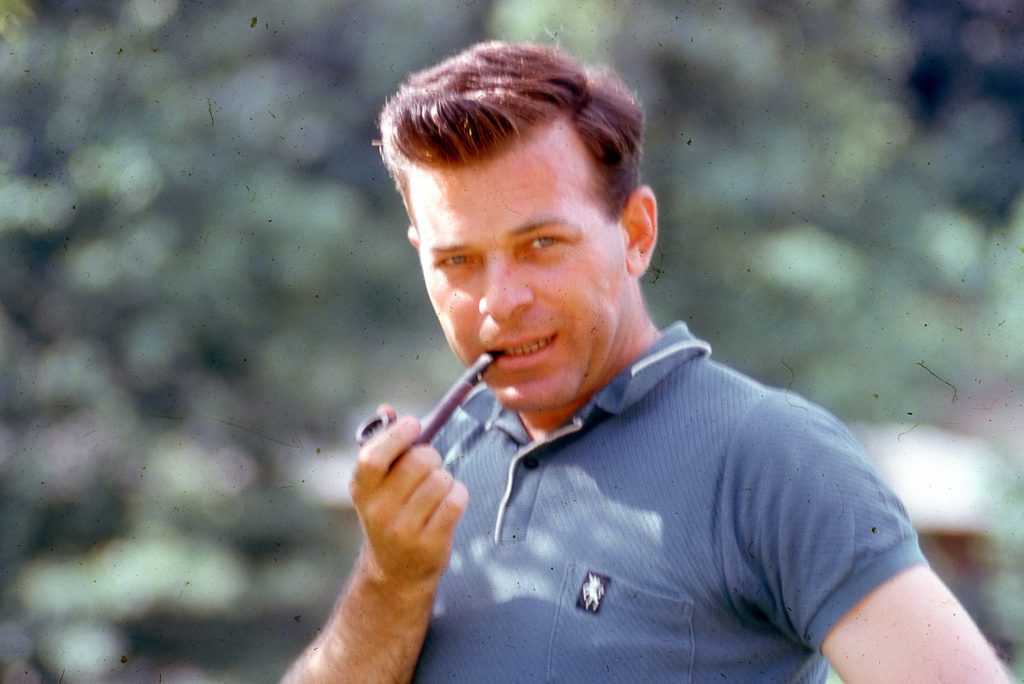

I had the pleasure of sitting in the Dining Car with Carol as we rode the FFV — the C&O’s famous passenger train, called “The Fast Flying Virginian,” from Charleston to Williamsburg in 1960, to visit her classmate Sherry McCormick and her newly-wed husband, Bob Harrison, who was also Carol’s high school classmate. Carol and I boarded the train in St. Albans very early in the morning. As we passed Sandstone Falls on New River (see “Camping and Fishing”) I practically thrashed her arms to get her to look at those magnificent falls, just west of Hinton, WV. The train trip was just idyllic. We had breakfast in the dining car, which — in accordance with historical precedence — was managed and served with the greatest of professional elegance. What a trip.

In about 1995, Carol, Amy (who at that time was employed in Washington, DC by the CSX Corporation, formerly — yes — C&O Railroad) and I went on a steam engine tour of the C&O trail from St. Albans to Hinton and back. We were with Roscoe Peters, a true C&O buff and family friend from the Kanawha Valley. Roscoe’s father was a professor at WV State College, and Roscoe was a lifetime friend / “blood brother” of Carol’s brother Keith Hopkins. Roscoe’s family had grown up on the C&O sidetracks at Hampton, VA, and Roscoe had later met Carol’s brother Keith in the WV Air National Guard at Charleston. During the ‘80s and ‘90s, Roscoe and Amy became fast friends, mostly due to Amy’s employment with CSX, for whom Roscoe had a deep emotional attachment. With the steam locomotive performing beautifully, that excursion was truly exciting for me — hearing the engine up ahead, seeing the smoke puffing out of the stack, looking out at the scenery — New River!, riding past Sandstone Falls. A memorable day.

I don’t know how to wind this little piece down, but as with other entries in these writings, I’ll stay true to my intent to give you an insight, not a treatise — although I could fill several more pages with stuff about “a long steel rail, a short cross tie,” as the song “Streamline Cannonball” goes. The C&O was later to become part of CSX, an international corporation specializing in transportation and container shipping. But even now, in 2013, one can occasionally spot an older train car with the blurred “C&O” in faded paint on its side.