It was the early Spring of ’56, and Don (my uncle Don Hale, three years my senior) and I talked about going fishing sometime. He lived in Pittsburgh, where he worked for U.S. Steel. Back then it was one phone call and one short letter to set it up. I told him New River was my choice; he agreed. We talked about possible camp spots, and I said, “Guy told me there are places to sleep out downstream from Hinton, across the river from the railroad. Let’s give it a try.”

We met at a small grocery store, bought a little food and set out. Friday night, as usual. Found a spot right on the water about 7 miles down the river, and made camp. Very rough. No shelter, no stove, no lantern. I had an army blanket; Don had a worn-out sleeping bag. Anyway, we made do and stayed until Sunday morning — Don had to get back to Pittsburg.

Based on that weekend, he and I worked up a trip the following spring. We rounded up Granddad Hale and Pat Hale — Don’s older brother, and set out down the same dirt road below Hinton. This time we found another campsite a little farther down. With a little more camp gear this time, including a tarp for shelter, we fished a while, had supper and turned in.

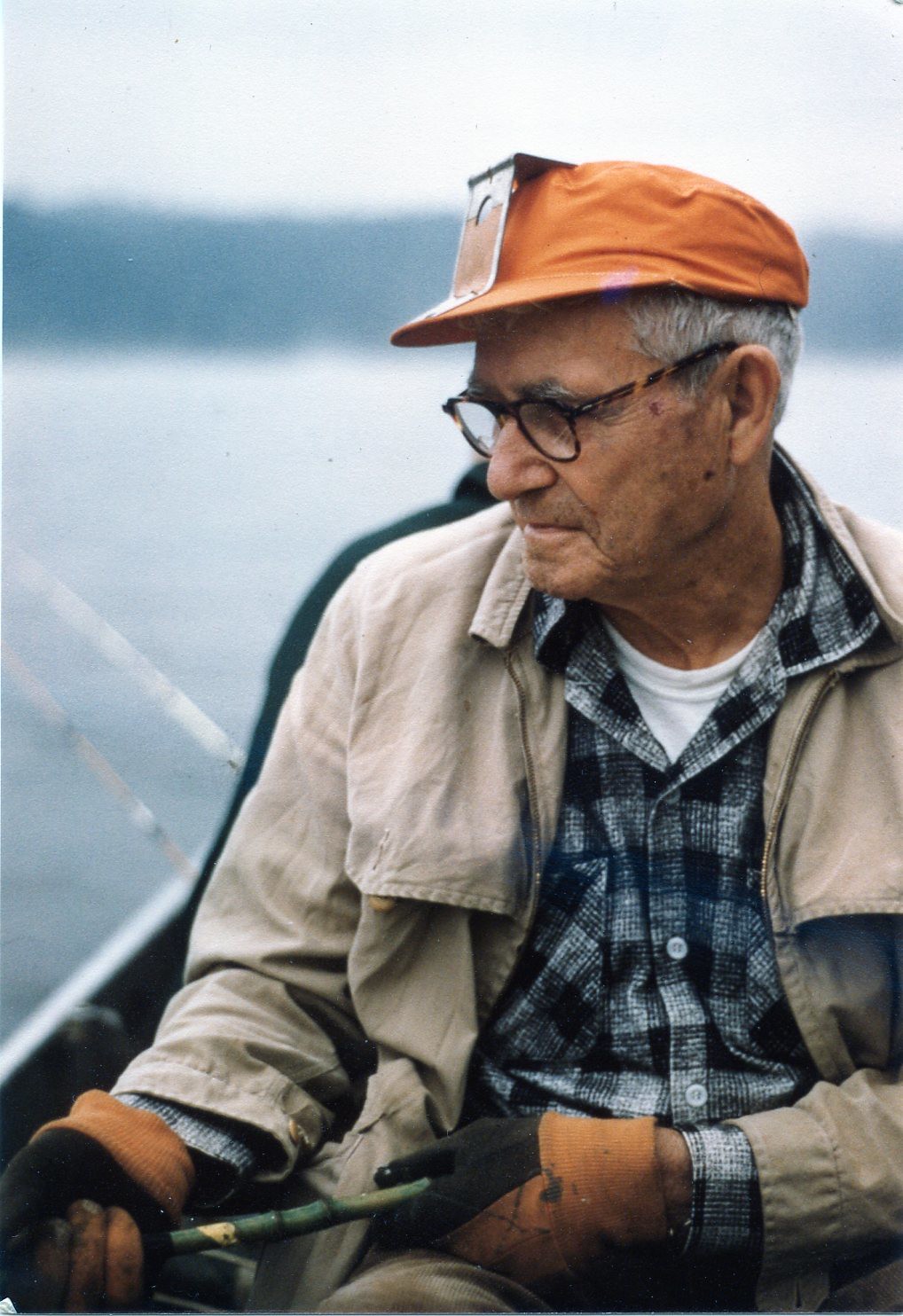

| Willis Farley, Patrick Farley – baiting hooks – Sandstone Falls, WV |

The next morning after breakfast, Don and I decided to scout downstream for good fishing spots, so off we went. We walked easily for about a half hour without seeing anything better than the site we were using. And then, well, let me do an “aside” here just to help you understand this story.

Flashback: It was Christmas time; I was about five. And we had a tree. I was in a trance with that tree. Every evening after supper I would go to the living room, lie on my back under the tree and just look up at the lights. I went through the same process each time: what is my favorite color light? Red? Orange? Blue? Green? And then it was Christmas morning. The lights on the tree. Gifts!!! Dad, getting ready to go to work at 7:00 a.m. David and Alice and I, open-mouthed, speechless, in a momentary wonderworld. Eyes popping. Mouths open. Hearts pumping. Breathless.

One of the best-remembered moments of my life, then or now. The feeling is not to be described, though most if not all little kids know it, but beyond words, though many real writers have come close.

So . . . that’s my “aside.”

| Sandstone Falls – October 1960 – Photo by David Farley |

Don and I walked around a slight bend in the road, and there, on our right the river. But what we saw hit me like that Christmas morning: awe. I was speechless. We both were. We had come upon, with no knowledge of its existence, that incredible sight on New River known as Sandstone Falls. Look at the photo; there’s no other way to describe it. Don and I were in a trance. Finally, he said, “Oh My God.” I agreed. So, on the spot, we decided that the campsite had to be moved. We practically ran back up the dirt road to our camp, and announced that we were moving down to the falls. Now remember, this was a two-night campout. When we got back to camp and made the announcement, Granddad and Pat were noncommittal, and we made the move. On the face of it, it was a dumb thing to do. But Pat and Granddad just had to see what we had seen: those roaring falls, with areas below to wade and fish; a perfect campsite, nature at its best.

Sandstone Falls became an annual destination, and along with the original four, our gang included brother Dave and my special buddies, Kenny, Louie and Lloyd. Every October we’d go to “Sandstone.” The days and nights there were unspoken magic to us all, and remain so in memory. While we continued to camp on Indian Creek — another kind of magic — Sandstone Falls was that place where upon discovery, at age 26, I was a little boy again, in my own wonderworld, just like being on my back under the Christmas tree.

Recently, Patrick and I were camping on Indian Creek (this is 2014), and we decided to take a drive down to Sandstone. I’d heard the story, and we saw it was true: the road from Hinton was no longer a dirt road; several years before it had been decided to pave that road, and to make Sandstone Falls a State Park. No more campers, no more fishermen, except for the family picnic guy, who occasionally walks across the State Park walkway across the river beneath the falls, and drop a line for a few minutes. We learned that few people go there; it’s just too far to see some waterfalls. So there’s a kept parking lot smack on top of our original campsite; a “park” up and down and across the area below the Falls, and that’s about it.

Paving that road put an end to an era: a place where it was free to camp, to fish, to watch the wonder of the Falls, and be bothered by no one save an occasional squirrel hunter. No surprise here: that’s been happening since the days of the early settlers, so I suppose I shouldn’t fuss. It’s just that when you’re the one with the Christmas Morning memory of that beautiful scene, it all seems kind of a magic-killer.

During those Sandstone years, I was having fun writing country songs about camping and fishing. There were several, the first entitled “Indian Creek,” which I sang to my infant children as I rocked them to sleep.

The song that became my personal favorite is entitled “When the Hales Take Over the New.” This is specifically about those times at Sandstone Falls. Here are the lyrics.

Note: “The Hales” is a reference to the entire gang, with Granddad Henry Hale being the patriarch, along with Pat and Don Hale, two of his sons, and David and me (half Hale, half Farley). The other guys were considered Hales by adoption, you might say.

When the Hales Take Over the New

Come October and we’ll all go

‘cross the river from the C&O

The leaves are falling and the water’s low

When the Hales take over the New, the New

When the Hales take over the New

Down the road to Sandstone Falls

It’s the time of year when the river calls

The fish are jumpin’ and you know it’s true

That you gotta be on the New, the New

Well, you gotta be on the New

Build a fire from an old crosstie

Build a fire from an old crosstie

Set your pole for a big red eye

That’s the very first thing you do

When the Hales take over the New, the New

When the Hales take over the New

Late in the evening when the fire burns low

You can hear Big Henry on the old banjo

Pickin’ out “Cripple Creek” and “Shady Grove”

And you know you’re on the New, the New

Well you know you’re on the New

The fog’s on the river and it’s late at night

When you’re on the trot and the line pulls tight

You got a cat and he’s a nice one too

And you got him on the New, the New

Well you got him on the New.

Come October and we’ll all go

‘cross the river from the C&O

The leaves are falling and the water’s low

When the Hales take over the New, the New

When the Hales take over the New