This is a standard blues song. The coal business in WV had gone south. It’s based on my uncle Pat Hale, who had lost his job and gone to Ohio with other coal miners looking for work. My brother David, who was truly gifted with words, helped with lyrics.

Author: Joplin Hollow

Indian Creek (1958)

I spent a lot of time camping at Indian Creek, and wrote this in 1958. It took 2-3 evenings to write it, and I sang it as a lullaby to Patrick as a baby.

This video features Alan singing this song from a recording made in 1965. The photos were all taken by Alan’s brother David in the 1950s and 1960s.

My Songs – Introduction

With a couple of exceptions, the songs included here are all about the woods and waters. Mostly about camping and fishing on New River and Indian Creek with the “gang,” Hanry Hale (called Big Henry in one song), his sons and grandsons, along with a few close buddies.

The songs were ‘written’ by me, with no intent whatever to perform them in public, or to record them for general distribution. Rather, the songs were for the riverbank, and were mostly written with a particular place and event in mind. I would take a “new” song into camp just to entertain us campers, nothing more.

It follows that I didn’t sing the songs for friends, neighbors or others. Not that I guarded their privacy — that’s just the way it was. I sang them now and then at home, and I played guitar likewise: now and then. I never played guitar with another guitar player, never even knew another guitar player, so you’ll understand that my technique was alive with wrong fingering, bad habits and no finesse. I never used a pick. Never owned a capo until I was about fifty. You would agree with all this if you were to watch me play.

So, the songs are what they are — injected with memories of individual camps, thrown together in time for the upcoming roundup.

I’ve long known that when it comes to my music I have a dual personality.

There’s the formal, classical side, in and with which I remain totally engrossed as a listener and “student.” (I haven’t played oboe or sax in many years, and my “formal” singing voice is long gone, replaced rudely by COPD.)

Then there’s the country side, with the southern mountain core — with a southern mountain family, it comes naturally. Growing up in town among country folk made good sense to me.

So the country songs are a matchup with the times in the woods and on the waters, embellished by the ever-present train whistle. Have a listen.

Wood

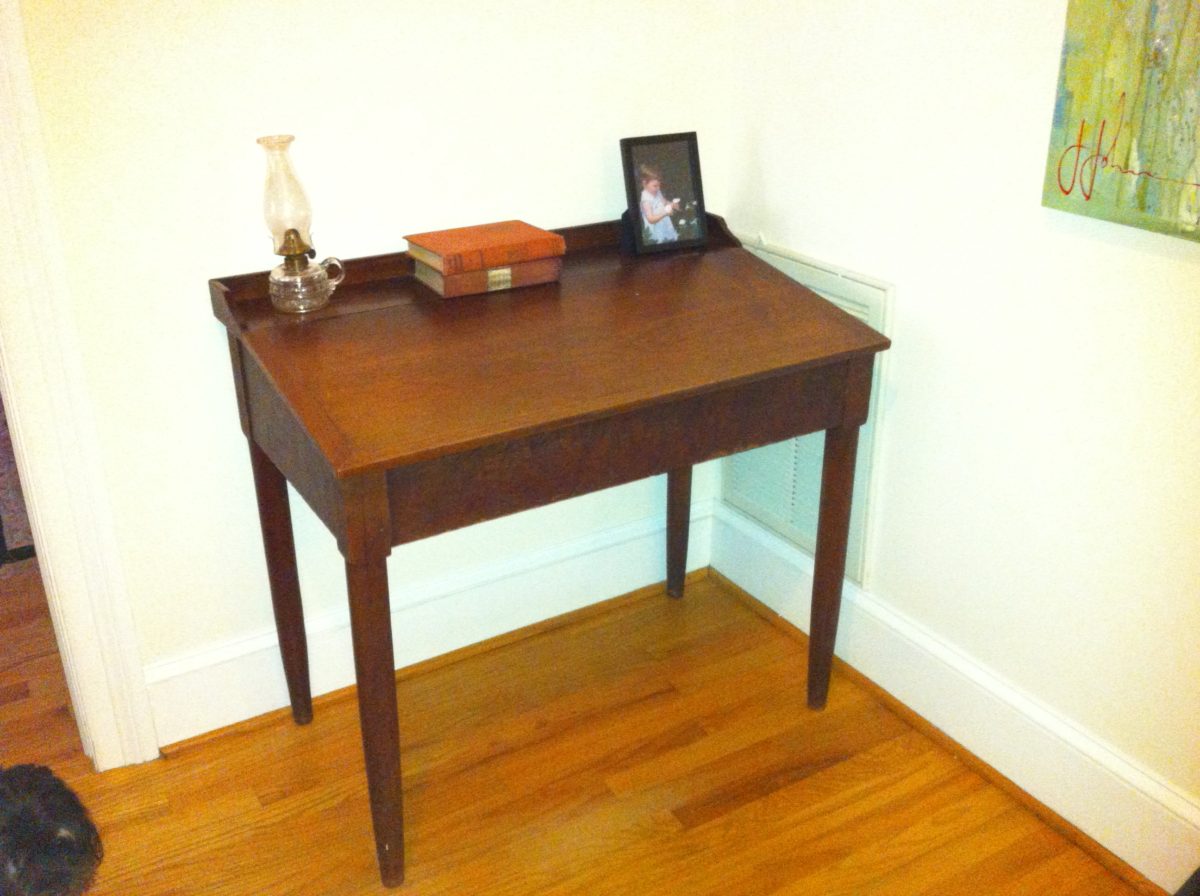

My great-grandfather Hite was a cabinet maker. He was truly masterful in his ability to work with wood. While I as a young child had heard of his skills, the only remaining piece of his making is a small lift top desk, which was in our home for many years. That desk was my work surface when I was in high school and college. When my family’s household items were distributed following my mother’s death, the desk came to me. Later, as Carol and I distributed our share of those belongings, the desk went to Leslie, and it stands in her home today. It is of black walnut, one of the most difficult of woods with which to work. Walnut is a beautiful dark, dense wood that improves with age. It needs no varnish, nor shellac, nor other finishes: only oil — boiled linseed oil rubbed in lovingly with rottenstone powder. You pour a small amount of warm linseed oil on the wood, then sprinkle rottenstone on it and proceed to rub it into the wood. The finish is remarkable: smooth, lustrous, water resistant. The more you rub it in the more lustrous it becomes.

And, of course, great-grandfather Hite was a latecomer. Woodworkers have been around for thousands of years, and when he came along, artisans had been at work for centuries at creating wonderful structures from wood.

You can bet that no modern wood is treated thusly, except by those few who remain dedicated to the handcraft-artisan breed. In my family, Dad and Paul made three walnut tables for us in 1959. At this date Patrick possesses the one remaining table. Made from black walnut, Dad gave them to us in unfinished form; they had been crafted and sanded. It was up to me to finish them. According to Dad’s instructions, I warmed the linseed oil, sprinkled on the rottenstone, and rubbed and rubbed, and rubbed some more. I was amazed at the result. And after 50 years of wear and tear, that table looks like new.

Such is working with wood. Dad was a self-taught, master craftsman at woodworking. He could replace veneer on an antique piece so expertly you could not — could not — find where the original stopped and his work began. In addition to a true love for wood — its touch, its feel, its smell — he had the skill to cut, shape, sand, fit, sand and fit again, so that the finished product was timeless and perfect.

What was the secret to his talent? Well, as I said before: he had the skill to cut, shape, sand, fit, etc. And his love for the essence of wood. Then came the true secret: patience. He would take weeks on a project, waiting endlessly between steps, with small touches of sandpaper or talc as the piece emerged from throwaway scrap to polished beauty. If you were to ask Mother, his patience was sometimes maddening. But, she would admit, it was his gift.

As a young kid, I watched without interest as he worked with wood. My thoughts were elsewhere, and to tell the truth, it seemed to me he was making it more a chore than a hobby. So my enthusiasm for woodworking was very low until Carol and I started housekeeping. Then it hit. Small projects came up, like building a shelf unit. I found that I could measure and cut pretty well, and little by little my skills improved as I encountered new challenges. It was inevitable that I “join the club.” Over the years, I have built many items with wood, including a few pieces of casework furniture for use in the house. While I never became a master, able to construct with the use of advanced joinery, or make full use of tools such as the router (I own one and can perform basic tasks with it), I can still take on a project which involves techniques I’ve never used.

Many of my works are gone: given away, donated, worn out and discarded; the usual end results. My most involved project was a three-piece entertainment center, built as a corner unit intended to hold a 32” TV set of the old-fashioned CRT type. We used it until the flat panel TVs became available. A 40” flat TV wouldn’t work with my cabinet, so I sold it.

I have enjoyed my power tools: table saw, drills, router, chop saw, jigsaw. They are very useful for most woodwork. And I know good woodworkers who simply like their power tools — the tools themselves, I mean. And I understand that. But I have enjoyed even more the hand tools: saw, hammer, chisel, knife, coping saw, hand drill. I know I’m one of countless people who simply find wood to be joyously attractive, and who take enjoyment in working very directly with it. By hand. Using hand tools and sandpaper and other media that aren’t operated by electricity or motors. To get the real feel of wood, it’s best to make that cut with a hand saw, or to carve with a knife, or to shape with a chisel. And to take sawdust between your fingers and smell it, and feel the smoothness of a piece ready to be rubbed with rottenstone. And finished with oil or other natural products.

To me, it’s not necessarily the product that satisfies as much as the wood itself: the grain, the color, the density, the smell and more. A piece of wood, well-seasoned, brings forth the senses in a way that is altogether pleasing. Learn to touch, feel, smell, see wood for what it is. Then you learn to admire — and respect — this beautiful stuff — the most important raw material on Earth. And then you feel you know a little more about people like great-grandfather Hite.

My time with wood has been one of my true pleasures.

White Silence

I think I was 15. Wintertime. Saturday morning. Snow about six inches deep everywhere. Nothing going on at home, so I decided to go out.

I walked through the snow down to the railroad tracks, then stepping on every cross tie to the South Charleston C&O Railway station. No one there, no cars on the street, no sounds. No sounds: if you’ve never been in cold country when there’s snow, you don’t know that kind of silence. It is absolutely arresting. I was already accustomed to the uniqueness of a winter day, so there was nothing about this particular Saturday morning, until memories crept into my mind, as they do with the advancement of years.

Incidentally, and of no particular importance except that it’s folded into this memory, I had been given a pack of Kool Cigarettes by a buddy. Kool Menthol Cigarettes. I had been smoking for a while, so I lit up. Wow! the sensation was something: the smoke was enveloped in a soft, wispy ball of menthol, far different from regular cigarette smoke. Standing on the railroad platform, smoking that strange cigarette, occupies a sliver of time in this memory.

Back to the event. The part that still lives with me is certainly not the cigarettes — it is about how nature in its beauty enters and stays in the mind. What I really got hooked on that frigid Saturday morning was the incredible beauty of the white, motionless silence, affecting five senses: sight, sound, hearing, touch, and vision. The impact on my awareness was something I had never before experienced, nor seldom since.

I looked around at the railroad tracks, the trees on the other side, with naked black limbs, standing in stony silence, A section of snow on a limb falling silently to the ground, no whisper of life or wind or movement. The falling flakes against the grey background of sky. It brings to mind an early black and white photograph. I think I knew then, and I surely know now, that my sense of the world was different from that day on. I am sure that if by some chance I find myself somewhere on such a day, that time long ago will reintroduce itself and I will go there again.

Whether at a train station, or by a frozen stream, or on a dark street corner, it is the same: a memory without adequate description, frozen in time. If you’ve been there you know what I’m talking about, and like me, if you’re stuck for words — I understand.

When the Earth Cooled

If you’re reading this say, forty years from now, like in 2054, you probably believe that age 82 isn’t very old. By then “old” may start at about 100. Until you stop and think about “the way things were,” as life-span thoughts get you caught up in the now and the then. So yes, I’m 82 and I don’t really feel very old physically, and my mind works at about eighty percent, and I laugh a lot, get around, and all the rest. But hold the phone.

At 5:30 this morning, while waiting for Carol to awaken at about 7:00, I was reading a nice mystery filled with the usual dialogue between the main characters. One says to the other something about a good radio station in a small town. Like, “Great station, the DJ plays all the oldies; James Taylor, Carly Simon.” James Taylor? Carley Simon? Yeah, I know who they are, but oldies??? Here are some oldies: Frankie Laine, Eartha Kitt, The Mills Brothers, Carmen Cavalerro. Dennis Day, Paul Weston, The Three Suns. The Ink Spots. Oh yeah, the Ink Spots.

So I laid the book on the sofa and continued the line of thought about oldies. Let’s see: country music. Anyone in their 50s would consider oldies to be performers like Garth Brooks, Alabama (“Ride the Train,” great stuff). Well, how about my version of country oldies? Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, Alonzo and Oscar, Faron Young, Ernest Tubb, Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers. Grandpappy George Wilkerson and the Fruit Jar Drinkers. The Chuck Wagon Gang.

Then it occurred that it has always been thus. I remember my mother saying something about Fatty Arbuckle, and Rudolph Valentino. To her, in 1950 or so, they were the oldies. To me they were mythical. And so it goes. So as I went through this exercise before dawn this morning, I began to feel it. Old. But I have a solution, and it’ll make me feel as young as I always feel in my mind. Well, not young, just Not Old. I’ll just not concern myself with what “oldies” really means. If you go back far enough, some person had no concept of the term. And then the earth cooled.

Dollars Stuff

If Patrick, Leslie or Amy is/was your great grandparent, you may or may not find the following easy to believe. While I’m sure you have observed the continual escalation of prices for goods and services, it only takes on important meaning after you’ve been around long enough to see just how much the purchasing power of the dollar changes over time. In my own experience, I didn’t pay much attention to money matters until I was in my thirties, and was struck by the increase in property values. The following may help illustrate this point.

I’ll start this with news about 1949, when I enrolled at Morris Harvey College, in Charleston, West Virginia, as a freshman. The tuition? $156.00 per semester. (Morris Harvey was a private, liberal arts college and could set its own tuition rates; all colleges within the West Virginia State College System charged a whopping $40.00 per semester.) While in school I worked on Saturdays as well as playing in local dance bands, and worked at summer jobs, all of which to get through school. (I lived at home and rode a public bus to school daily — from home and back for 20 cents.) One job was to report to a men’s clothing store on Saturday morning, and demonstrate a Sunbeam electric razor to customers who were browsing. I worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and earned $10.00 for the day. Then I’d play a three-hour dance job with a local jazz group, and was paid the union wage of $8.00 for three hours. Most weekends I played both Friday and Saturday nights.

The federal minimum wage in 1950 was $0.75 per hour. That’s what I earned working at the Union Carbide plant during the summers, and that came to $30.00 per week, minus taxes. That, plus my earnings during the school year, pretty well paid for my college degree.

During those years I was in the 425th Army Reserve Band, which met weekly, and had active duty for two weeks every summer. I received regular army wages — prorated, of course, which were paid every three months and amounted to something like thirty-five dollars.

Then we go from there . . .

As I said elsewhere, I paid $2,100 for my first car, a full-size sedan. That was in 1953. I remember that, earlier, when I was about nine, Chevys and Fords cost around $800.00.

My first annual salary as a school teacher was $2,700. That’s annual. At that time in West Virginia, there was a state salary schedule for classroom teachers, which local school systems could exceed but had to meet the schedule as a minimum.

The schedule called for an annual monthly increase of ten dollars each year for twelve years. As a band director, I was paid an extra thirty dollars monthly for extra duty: ball games, concerts, etc. We received nine monthly paychecks a year, so I either had to get a summer job (not easy) or save during the year to make it through the summer months. Of course, I continued to play in dance bands — the pay had gone up to $12.00 for a three-hour job. I worked with another summer employee who was a full-time student at West Virginia University. He said he could pay for a year’s schooling, including tuition, books, fees, food and lodging for about one thousand dollars.

I started a Master’s degree program at Ohio State in the summer of 1956, but I don’t remember the cost. In 1957 I decided to go to Teachers College, Columbia University, so I started over on the M.A. At Columbia, the tuition was outrageous: $30.00 per credit hour. That fall, Carol and I were wed, and I continued my summer program at Columbia, finishing in 1959. How did we do it? The local Bank of St. Albans had a program for school teachers: one could borrow $1,000 to get through the summer, then pay it back at an easy rate during the school year. That one thousand dollars paid for my second and third summers’ school costs.

I won’t take this piece much farther, but here are a few other tidbits about money.

In 1963 I changed jobs and we moved from St. Albans to Salem, Virginia. In order to do so I cashed my retirement contribution to the West Virginia retirement system. Total contribution during ten years: $1,800. That’s a hundred and eighty dollars a year — twenty dollars a month for nine months. That eighteen hundred paid for the following: the moving van, which we shared with our friends the Parsells who moved with us; a second car — a used ’56 Oldsmobile; Carol’s hospital costs for giving birth to Leslie; and a down payment on a house the following spring (the house, on Youngwood Drive, cost about $15,000). We could buy three pounds of hamburger or sausage for one dollar. I could buy a pack of cigarettes (I was a smoker back then), a loaf of bread and a quart of milk for a quarter each. The hospital bill for Amy’s birth (1967), was about $500 — paid in full by insurance. Our mortgage payment was about $160 per month. My salary in 1963, based on 10 years’ experience and a Master’s degree, was about $6,000.

Not able to be among you, which I regret, I haven’t even speculated about what your cost of living might be as you read this, but I’m sure you’ll find that whatever you earn, it is just a living. It was that way with us; with Carol’s uncanny family finance skills, we always had enough to get along, with a little extra for emergencies or good times. And from age 11, when my Dad cajoled me to cut neighbors lawns for 25 cents, until I retired at age 65, there was never a time that I didn’t work for wages, so yes, I was and am today conscious of “the dollar” aspect of life in our times.

Computers

I don’t know much about computers. Compared to today’s 12-year-old, I’m an ignoramus. I come from a prehistoric generation, when phones were connected by wire, when electric ovens were new, when there were no cell phones, no smart phones, no email, no texting, no caller ID, no call waiting, no message phones, no answering machines, no internet — you got it: none of that stuff. In my time, the telephone was magic. You could dial a number and get an answer. In our case we had a “party line.”

That was a deal where several “parties” shared a common phone line. If you picked up your phone and your neighbor, a “party,” was using the phone, you hung up and waited. Or if you were on your phone and you heard a “click,” you knew someone on your party — among several sharers on that one phone line — was listening in. You can imagine the responses: “Linda, are you listening in on me?” Click. Linda’s gone. If you needed to make a crucial call, and someone was on the line, you’d have to ask Drema, or John, or whoever, to please hang up; you have a crisis call to make.

The phone numbers in South Charleston — an upgrade city, because of Union Carbide — were 5 digits long. Our number was 42807. No prefix. No sir. Of course the phones were rotary dial phones where you had to put your finger in a hole corresponding to the number you wanted to dial, then swing it around to the right and let go. You got that? I didn’t think so; the technology was beyond your grasp. Haha.

After dialing each number in that manner, you’d get through. If you were lucky, and no one on your party was listening in. Which they did, old biddies. Eventually, communications technology improved. At some point, about 1954, they added prefix numbers. Like, “Pennsylvania,” numbers “72,” etc., which denoted the first two digits of the number to be dialed. Of course, this was in place in New York City long before our WV time. Consider the Glenn Miller tune “Pennsylvania Six Five Thousand.” That was a phone number of the hotel the band stayed in, back in the late 1930s. It was the number of the Pennsylvania Hotel, and the band decided it was worth a song title. So our West Virginia system in the late ‘40s was about twenty years behind the times.

All that said, look at the history of computers dating back to those times. And then came WWll, and the development of even more sophisticated communications and data storage equipment. Finally, in the 1950s, the famed IBM 1401 series pretty well revolutionized the communications/storage/computer age.

The reason I say all this is that I’m still amazed at the computer age. When I was working in Roanoke County Schools on our scheduling project (written up elsewhere here), we had an IBM 1401 computer. Archaic, yes. Capable, yes. I even took a course in programming with the 1401 language: Autocoder. The input was by punched cards, and each card had to be manually punched — and then manually verified. No such thing as a computer keyboard. The mouse hadn’t even been dreamed about. And it worked for us. But we needed much greater computing power for our project, and worked a deal with Virginia Tech to use their system, a state-of-the-art lab with the latest equipment. Our scheduling package required an astounding — yes, I said astounding — 128K of usable workspace to generate a high school master schedule. I have no real idea what 128K means today, since everything is measured in gigabytes or terabytes, thousands of times more powerful. The VPI computer system (IBM Series 360) capability was, I think, 256K. Unreal. And the computer lab consumed about 2,000 square feet of space, housing the mainframe computer, the card reader, disc drives, tape drives, and all, resting on top of an under-the-floor myriad of cables, air conditioning, and so on. It was a huge space. Today, that same capability can be housed on a small desk. And we’re still in the embryonic stage of computer technology.

I surely don’t mean by any of this to profess any knowledge or vision about computer technology. In the 60s, I was able to understand the parameters as well as the specifics of our computer package, which was actually a set of programs created at MIT; I could provide input in proper form; I could keypunch cards accurately; I could read the input stream to a computer, gather and trim the output, analyze the reports, make changes in the input, initiate the next run, look at the next outputs, etc. etc. Most of that was mechanical stuff. My only real skill was in reading and interpreting the outputs; making decisions that would improve the final output, which translated into good results for kids in their academic programs. I could not write code except on a very basic level. I could not have discussions with tech support personnel. I could not tell you anything about hex programming and other weird stuff. In short, I was never, and never will be, a competent computer person. So I guess I had just enough knowledge to be a pest. And I refused to be that, so I tried my best to work with Tom Farrell, the former IBMer who knew how to make an IBM 1401 turn cartwheels, providing him with educator-based calls on what to change or keep from a particular computer run, in the interest of good schedules for students, computer be damned.

In 1981, while serving as superintendent of Greenbrier County Schools, I became aware of the new kid on the block, the Apple. At that time there were virtually no computers in classrooms except in specialized programs such as vocational education. But the Apple changed all that. I suppose my enthusiasm was borne of my personal experiences with data processing, but whatever the reason, I was able to initiate one of the first school computer labs in the state. Oddly enough, I left my position that fall, and never got to see the results of the hard work it took to convince people that computers were “here to stay in our schools.” Of course, the rest is history.

Today, the iMac I’m writing on has more power than that lab at VPI in 1968. I suppose I should be astounded, and in some ways I am, except that I am also cognizant that we’re on the burning edge of something we can’t even imagine. I’d love to be around in another 80 years; it’s going to be a time to make all of today’s capability appear as ice-age stuff. Except for the ‘human’ element, which will not go away. So, I was born before the computer age. I participated in it to a limited extent — but far more than most of my uninitiated contemporaries. I learned to respect it, to acknowledge it, to rely on it in controlled situations, to admire it, to fear it, but never to embrace it fully. Yes, it is a time of marvels. But when was it not? So then, what comes after computers? Wish I could be around for that, to act like a curmudgeon.

The Desk

William Hite was my Dad’s maternal grandfather. He was born near Staunton, Virginia, and was a Civil War veteran — on the confederate side. He married a much younger Alice Jameson in 1875, and in his adult life was a cabinet maker. In the 1920s he and Alice lived in Alderson with Granddad Farley’s family. William died in 1926. Notably, from a family standpoint, he made a desk.

The desk came to our house in South Charleston, West Virginia sometime close to Alice’s death in 1941. It had been in the Farley house in Alderson, apparently brought there earlier by William and Alice in about 1920. I honestly don’t when we got it. In any event, the desk was an important part of our Sycamore Street living room from about 1940 until Mom and Dad moved the family belongings to their new home in St. Albans in 1961. It was very much at home there until Mom died in 2001, at which time it went to Leslie’s home in Raleigh.

As the photo shows, the desk is not large. It has a sloped lift top, beneath which the storage area provides space for what was, during William’s time, adequate for personal and business items. At the back, the lift top gives way to a narrow level area, which I suppose was where ink, quills and other small items were placed.

The design is simple, graceful, yet extremely functional. The slender legs are easy on the eye, and the desk’s overall appearance is appealing. Made of walnut, it has been and is today as sturdy and tightly joined as it was more than seventy years ago when we first became friends, the desk and me.

I don’t remember seeing mother at the desk, except to occasionally use the phone. Dad, of course, kept the family’s business papers, such as they were, in the desk, and would routinely raise the top, go through the papers frantically, then with frustration barely beneath the surface, ask Mom to find whatever he was looking for. But his stream of Letters to the Editor regarding a variety of political matters, but mostly on the environment, the single mission of his later life, was composed at the dining room table, where he could spread out the newspaper — for reference to the latest editorial — along with his legal pad and assorted documents.

For several years the phone was the only item permanently on the desk; then at some point Mom or Dad put a gooseneck lamp there, which really helped if I was doing homework (a rare event). Alice, of course, was the studious one and used the desk — and lamp — almost daily. Our only house phone (back then no one had more than one phone) rested on the back of the desk. During those early “desk years,” if I picked up the phone to make a call, it was likely that I’d hear voices of other users on the phone line, or party line as it was called. Our “party” consisted of five families, all sharing the same phone line (although of course we had separate dial numbers). There was one lady who gossiped nonstop with anyone who would take her call, and if we would politely interrupt and ask her to free the line, she would simply keep talking.

Party lines were quite common, and most everyone had the same tale to tell about the one person who talked constantly. Mother taught us to always listen for a clear line before dialing. I didn’t use the phone for idle talk, but I could call Kenny Pulliam, phone number 42473, to confirm an evening out, or Kenneth King, phone number 43878, about a school event. Stuff like that. During those teenage days there were at most a half-dozen people, all classmates, with whom I talked on that telephone. That was the norm for all of us.

As for me, the desk was, well, comfortable. Not that I liked it the way one likes a puppy, or another person, but it was close to that. The small stool which stayed underneath it when not in use (we called it “the telephone stool” forever, and it is still in the family somewhere) was just the right height and girth for desk work. So although I was too inanely carefree to be a real student, much less a young scholar, the desk prompted me to sit, write, read, talk, do all those things that lead to growth. Later, when in college, I thankfully became serious about learning, and the desk was even more my home base for digging around in my mind. I especially remember working on music — working through figured bass exercises, analyzing harmonies and counterpoint, fussing at Bach, studying Italian musical terms, and so on. And term papers! Damnable all, term papers on topics long forgotten.

From time to time I think about how William Hite must have bent his mind and hands on that project, built without the many woodworking tools and implements of later times. Using a hand saw, block plane, draw knife, awl, foot-driven lathe, and so on, he created with a true artisan’s touch a piece that has been at once both highly attractive and useful; a piece remembered by all the Farleys with thoughts of pride and appreciation. Today it stands in Leslie’s home, as graceful and stout as ever, ready for the next customer. So thank you, William Hite, for a lasting gift that has brought pleasure to our family for more than a hundred years. May it remain a Farley prize for yet another hundred. There are those — and they are many — who believe that “Why, certainly, one can have a relationship with almost anything — flowers, people, a book, perhaps even a beetle: you name it.” And so it is, happily, that I and probably several others have had — and still have — a relationship with a desk.

Guitars and Dogs

When it comes to a companion, I’d rather have a guitar than a dog. Now I’ve had dogs, and I love them. And my kids have had dogs, and their kids. Dogs are all that is written about them, and “man’s best friend” is a good descriptor. But here’s the thing: A guitar doesn’t poop on the rug, run away, bark at neighbors, have to be fed, bathed and combed, and all that other stuff that goes with a dog.

Just by strumming a chord or a string of single notes, a guitar shares with you its beauty. You can pick it up and set it down at any time of day or night and it won’t mind. It contains all your songs, your musical dreams, your soul. And if a relative or anyone else plays it, those notes are held in memory too. Just like a dog, you can talk to it. It will last for years and years, and is always there, never complaining, just waiting. And when you won’t be around any longer, you can leave your guitar and all the music you have planted in it to someone else and it will be that person’s lifelong companion, always reflecting everything about you. I’m not sure that works with dogs.

And it’s not just the music part that makes a guitar: it’s the physical guitar itself; its shape, size, finish, design, beautiful wood composition, the box and neck: in short, all that comprises the instrument. A guitar is lastingly lovely to see, lying on a sofa, resting in a stand, leaning against a tent, wherever it happens to be. Add these wonderful features to the artistry, the sound, tone, and musical potential that’s always there and you have the complete package. So give me the guitar. I’ll love your dog, pet and feed your dog, even sleep with your dog, and let the dog look soulfully into my eyes, whimper its best-friend love, and protect me against people who mean me harm. That I will of course love. Sincerely. But in the end, it’s the guitar. I just can’t help it.