“The Farm” was in Raleigh County, near a small mining town called Princewick. My Hale grandparents lived there and raised most of their children in the rather large house with white siding and a large screened front porch. From my earliest memories, the Farm was a magic place. Of course, by then we lived in South Charleston, and visited our grandparents only a couple of times a year — or so it seemed. Uncles Pat, Joe and Don, along with aunt Rook, still lived there, so it was a full house. Granddad was still working in the mines, as were Pat and Joe.

Outside, there were several acres of hilly farm land. They had a couple of milk cows, chickens, pigs, a grape arbor, a large garden. Out back the property sloped down toward a gully — a “wet weather creek.” Immediately behind the house were a granary, tool shed, chicken coop and woodshed. Further back and down the slope, away from all other activity, was the outhouse/privy, and on a rise about seventy five yards to the right was a large barn.

Inside the house, a wide hallway went from the front door to the back porch. These hallways were common then, called “dogtrots.” On the left front was the living room, with bare wood walls and little decoration. This room was rarely used by the family — most of the time was spent in the kitchen and dining room, farther back on the left. On the right side of the hall were stairs, and two large bedrooms, each with an open fireplace. (There were fireplaces throughout which were coal-burning and the source of heat for the house.) Upstairs were three bedrooms. I always slept on the living room floor (a treat I loved), and don’t remember anything about the upstairs. The back porch was a work area, and a place for the coal bucket/shovel, churn, kindling, water bucket for drinking water with a dipper, wash tubs, etc.

There was no indoor plumbing; water came from a dug well (as opposed to drilled) in the back yard, with a crank handle to raise the water container. As I said earlier, heat was from coal in open fireplaces, along with the wood-burning stove in the large kitchen. But — there was electricity, so there were lights, and a refrigerator in the kitchen.

No bathtub. Instead, a large galvanized wash tub. They would place the tub in the middle of the kitchen floor, pour in heated water from the stove, and bathe. I distinctly remember one time when Joe and Pat had both come home from the mines, black with coal dust, along with sweat, grease and dirt. They went to the kitchen, pulled a cloth curtain across the door, and took a bath. Before they started, they flipped a coin to see who got to go first — easy enough to figure that out. I was about seven at the time, was in the kitchen with them before I got chased out. Thinking back, it’s understandable that they wouldn’t refill the tub after each bath — that would mean extra trips to the well, etc. Can you imagine a family of ten taking baths in the kitchen? But Nanny was the original “Little Dutch Cleanser,” and her children, like her home, were given the spotless treatment.

I guess that was the family routine for a lot of years. In today’s world it’s hard to imagine that many people lived like that when I was a small kid. And unless you think about it, it wouldn’t occur that things were that way. (I note here that in today’s America there are still many people whose circumstances are as described above, and you can find in West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky whole communities of abject poverty. The shame of a nation.)

The Farm was a place of constant activity: menfolk going to and coming from the mines, Nanny in the kitchen constantly, daughters helping with housework, never-ending cleaning. All this along with the summer garden work — about two acres of vegetables which were worked by shovel, hoe, and pitchfork — no motorized tractor in sight, only a workhorse for the plow. Once the crops were harvested, the work of canning the vegetables began. a large open fire was built in the backyard, and a huge washtub of water was put on to boil the glass jars. The women would then take the sterilized jars to the back porch and fill them with all manner of food, from beans to corn to peas to carrots to pork to chicken and on and on.

During those summer months, the garden workers — that was everyone who was available at the time — would go to the fields early, work until midday, and go to the house for dinner (lunch). Nanny would have cooked fresh pole beans and new potatoes together, tomatoes, some kind of meat, and bread: either cornbread or leftover biscuits.

A very full meal for people who were working really hard. Supper would often be more of the same. Of course, there were jams, jellies, honey, etc., so the meals were both filling and tasty. As a small boy I was wide-eyed about all the stuff that went on, and although they wouldn’t let me work in the garden, I could get a real feeling for the farm atmosphere. How else to raise a large family on coal miner wages?

Mother told me more than once that it was her job to bake biscuits every morning, before daylight, of course, for the men who were going to work in the mines. She started this responsibility when she was eight years old. And she said that there were days when she would bake as many as six dozen biscuits. (At that time there were eight children living at home.) Those of course, were for both breakfast and the lunch “buckets.” A lot of hungry men. And many years later, her biscuits were still simply as no other. Light, browned on top and bottom, fully cooked, waiting for butter and/or honey, consistently the best biscuits I ever had. The difference, among other things, was lard. Those biscuits were mixed with lard: not Crisco, not anything else. Lard, rendered from the hogs that were killed each late fall on a cold hillside, with the help of neighbors who in turn killed their own hogs. Pork fat was in those days a most cherished product, used for many, many processes in cooking. Try to find lard today, in your favorite food store.

All in all, even for those times, the Farm was a little rustic. But it was a beloved home place to Henry, Effie and their large family — ten kids. My mother told me one of her earliest memories was waking up to the sound of Granddad working the coffee grinder — you’d enjoy seeing a picture of one of those; quite antique. And then smelling the coffee brewing on the wood stove.

I spent most of one full summer at the Farm. I was ten, I think. I was ecstatic to think about a whole summer. Of course, my uncle Don was there; the older uncles and aunts were grown and gone, although they would come and go, sometimes just to pitch in with the work. But that was the summer that Don and I connected; bonded, as they say. He showed me how to use an ax, cutting kindling in the woodshed against the winter need; doing daily chores like getting water from the well, collecting eggs, feeding the farm animals, milking the cows, exploring the farm buildings, playing with the two hounds that lived in the side yard . . . just being a couple of young farm boys. I learned a little about what life on the farm was like. Constant work. He was 13, so we were close enough age-wise to get along like a couple of cronies. What a summer. I cried the morning Nanny said goodbye and we walked through the fields, chill and covered with dew, to Princewick where we caught the Greyhound bus for Charleston and home.

Little did I know that life would never be the same: the Farm would be no more.

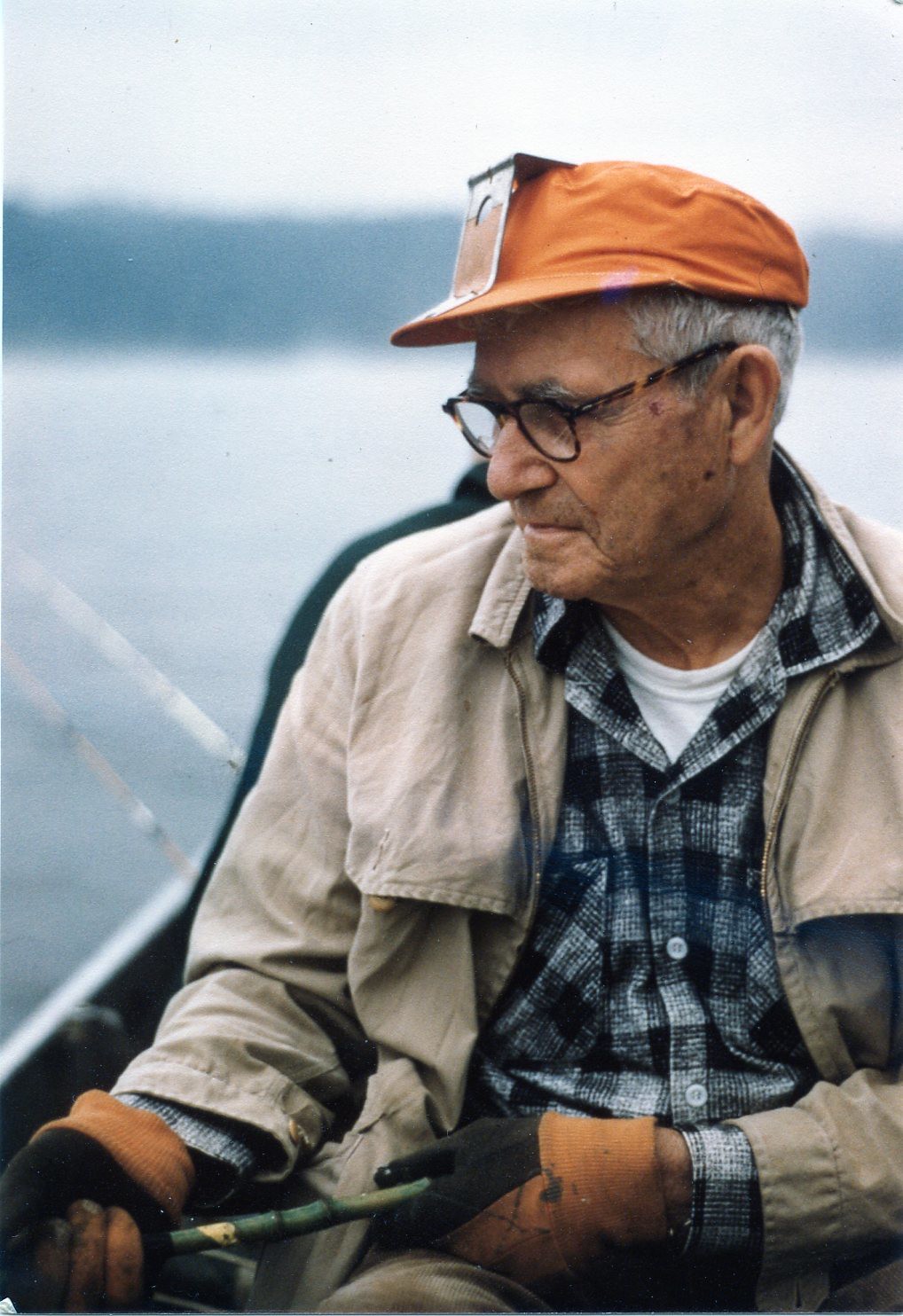

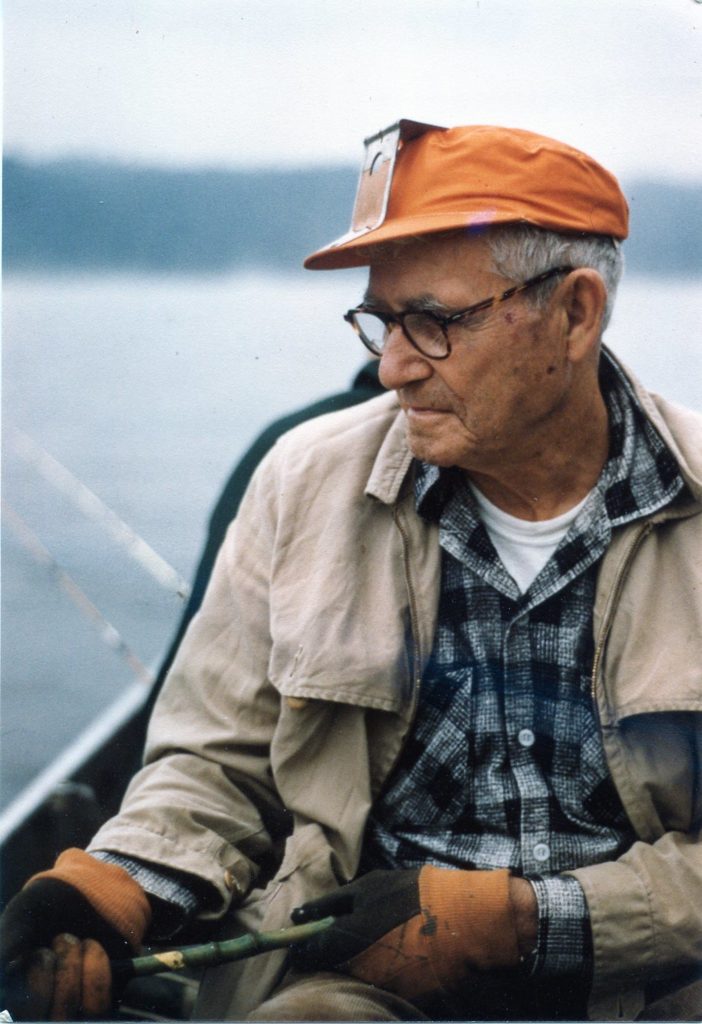

| Don Hale at The Farm – about 1938 |

I may have visited for a weekend a time or two, but that summer experience was never repeated — the Farm was on a limited lifespan. In about 1943, Nanny, Granddad and Don left the farm and moved to South Charleston, where Christy and Edith had purchased a small home for them in a community called Rock Lake Village, in Spring Hill, WV, just outside South Charleston.

Nanny and Granddad were no longer young; the children were gone, and life on the Farm had become a burden — especially with the infirmities of advancing age lying in wait. Nanny looked out her small kitchen window across the rooftops of the community and cried, every day, for years. In her mind, she still spoke to her beloved animals, the wood stove, and the rest. Granddad had no woods to walk in, no chores, no dirt to rub between his fingers, no wildflowers to gaze upon, no wood stove to fire up in the mornings — all that was gone. Although I know it hurt him terribly to leave behind a life that was so full of challenge and beauty combined, he was stoic about it, and I came to understand that he kept up a positive countenance, mostly for Nanny’s sake.

For me, an occasional visitor for just a few short years, the Farm has been an important part of my life. I can only imagine what it was for Nanny and Granddad Hale and their family: the life, the burdens, the challenges, the rewards. The hilarity, the #6 wash tub baths, the winter night trips to the outhouse, the frantic bustle of eight or ten people living there at once, the constant, never ending, grinding, ubiquitous work. But because I was there briefly, and of the wonders shown me by Nanny, Granddad and Don, I’m not that far from knowing, and that’s a good thing.