I was ten, I think. I had, during the previous several months, become addicted to hillbilly music, as it was called then. I had been kept home from school with a sore throat that wouldn’t go away, so during the long afternoons I would listen to local radio — AM only, of course, and country music was the fare. That led to my discovery of The Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights, so I soaked it up. The sound of a mandolin really got me. Banjo, fiddle, all the rest. I listened from 7:30 until the final show closed at 11:00. That final show was a thirty-minute segment featuring Roy Acuff and the Smokey Mountain Boys. He was famous at the time, and had several big hits to his credit. They billed him as “The King of Country Music.”

I could go on and on about the Opry, but this is a more narrow story. It’s about Roy.

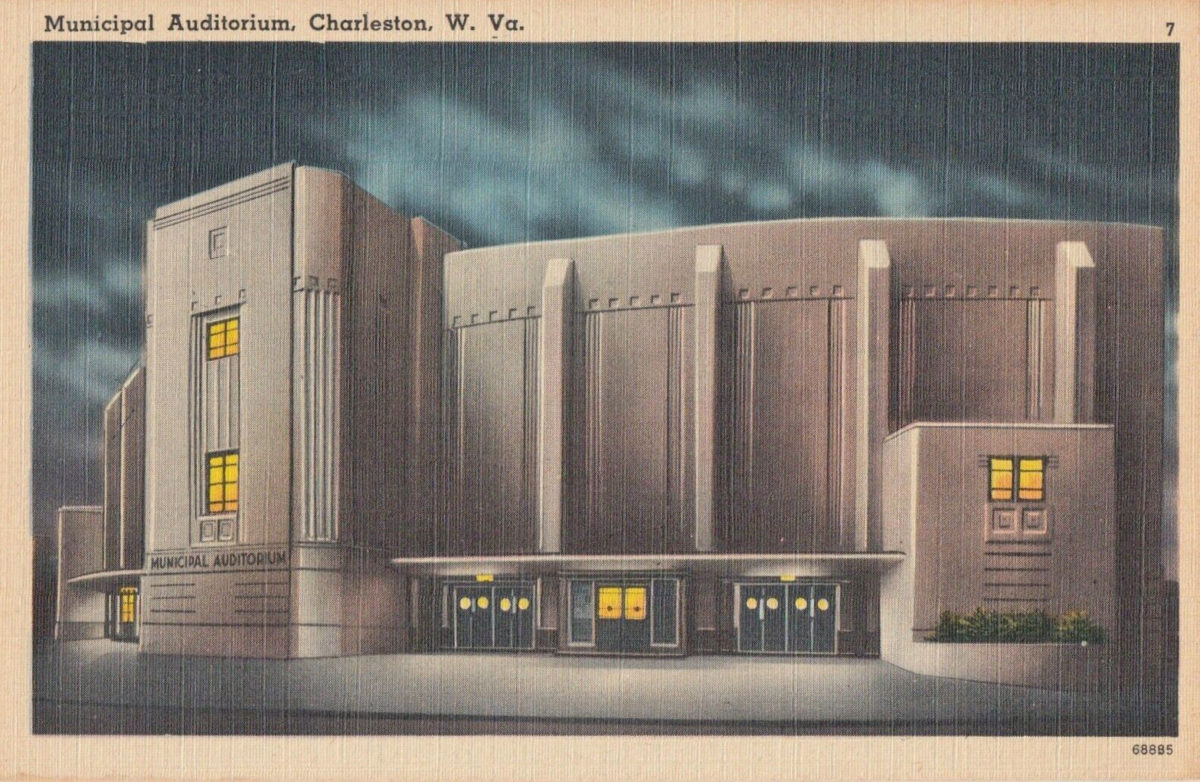

The ad hit the Charleston Gazette: Roy Acuff was coming to town, to the Municipal Auditorium, on a Sunday afternoon, in just three weeks. I whooped. Asked Mom if I could go; told her I had saved enough — well, almost enough, to buy a ticket. She said that wouldn’t work, she didn’t think I should go all the way to Charleston on the bus by myself. I begged. I pleaded. Finally she said OK. (I think she intended all along to go for it; she just wanted to impress on me the importance of taking care of myself.) So, along with the few cents I had, I saved enough for the ticket, with a dime to spare. I think the ticket was either 50 cents or a dollar, don’t remember which.

That Sunday, I dressed in my best green sweater, caught the bus. Bus driver looked at me, a small kid, asked where I was going. Puffed up, I told him “Municipal Auditorium.” I sat right behind him, looking out all the closest windows. He said “Here we are,” I got off in front of this monstrous building with all these people out front, and momentarily froze. Then I got my nerve up, bought a ticket and went inside. A cavern. Dark, huge. I found my way to the top, where there weren’t any people. I moved down two or three rows and got my seat. There was no one even close. I waited and waited, then finally the curtain went up and the show started.

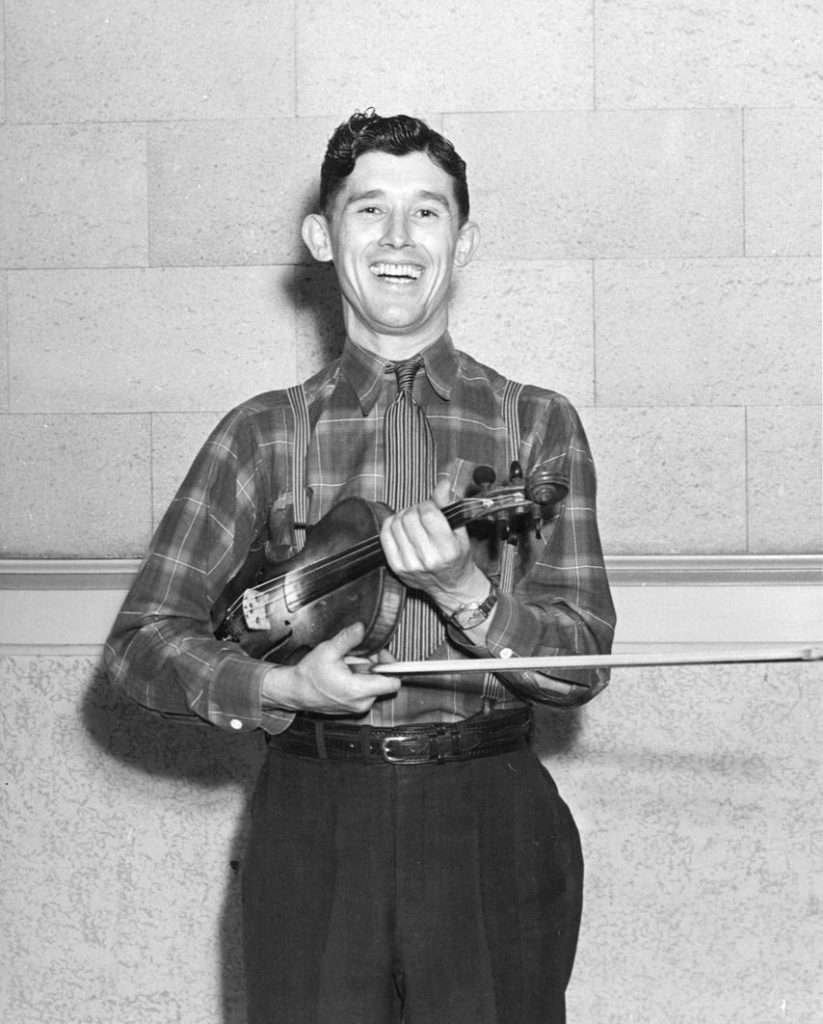

The first act on the show was a fiddle contest. There were two “finalists.” The first was a country guy called Natchez the Indian. Evidently, he was famous and traveled with the show. His competitor was a local man named Clark Kessinger. The crowd roared at his introduction. Someone could write a short story about that fiddle contest. I’ll keep it simple. Natchez went on first. He played an old-time hoe down, and everyone clapped. Then he did his big number: “Listen to The Mocking Bird.” He made his fiddle sing. Pretty bird songs, nice fiddling in between. Up the fingerboard, back down. Tremelo, acrobatic stuff. I was entranced. When he finished he received a huge applause from the crowd.

Then Clark Kessinger stepped up. While Natchez had come out in a fancy costume with spangles and a wide hat, Clark stepped up to the microphone in black trousers, white dress shirt, no hat. He proceeded to play his regular fiddle tune, matching Natchez with fast-flying bow work, all over his fiddle. The audience yelled its approval. Then Clark stepped to the mike and said something like this: “Natchez is a fine player. But he played ‘Listen to The Mocking Bird,’ which I had planned as my feature song. So if you all don’t mind, I’ll go ahead and give you my version.”

And he did. He not only played the sweetest, various bird songs, interspersed with a fiddle version of the song, he then put the fiddle behind his neck and continued to play. Then the fiddle went behind his back. The crowd roared. By that time I was transfixed. Finally, he took the bow, placed it between his knees facing forward, and played by moving the fiddle upside down, back and forth. That did it. The crowd rose to their feet, Clark took a portly bow and walked off stage. Of course he was named the winner of the fiddle contest. By that time I was in a trance.

And then: then, the show started. Out came Roy Acuff himself (also in dress pants and white dress shirt — none of that cowboy stuff — and the music began. The Smoky Mountain Boys played and sang all the familiar hits that I’d been listening to on the Grand Ole Opry. I can name the songs, the band members, the comedy, all of it. But that’s not important here.

I simply can’t tell you how I felt that day. I suppose “magic” fits. That I can tell you about it now, some seventy years later, may help you see me, young, green sweater, with a dime left over, going to Charleston alone, seeing and hearing all that music, forever tied to that kind of music. As it turned out, not just that kind of music. That was in fact my first “live” music experience. While I loved listening to the radio, the live experience made sense of it all. Music is music, in the end. Roy helped me understand that. Note: It turned out that Clark Kessinger lived in South Charleston. I went to high school with his son and daughter. Clark was locally famous, and in his later years won national championships for senior fiddlers. I have many of his recordings. Look him up.