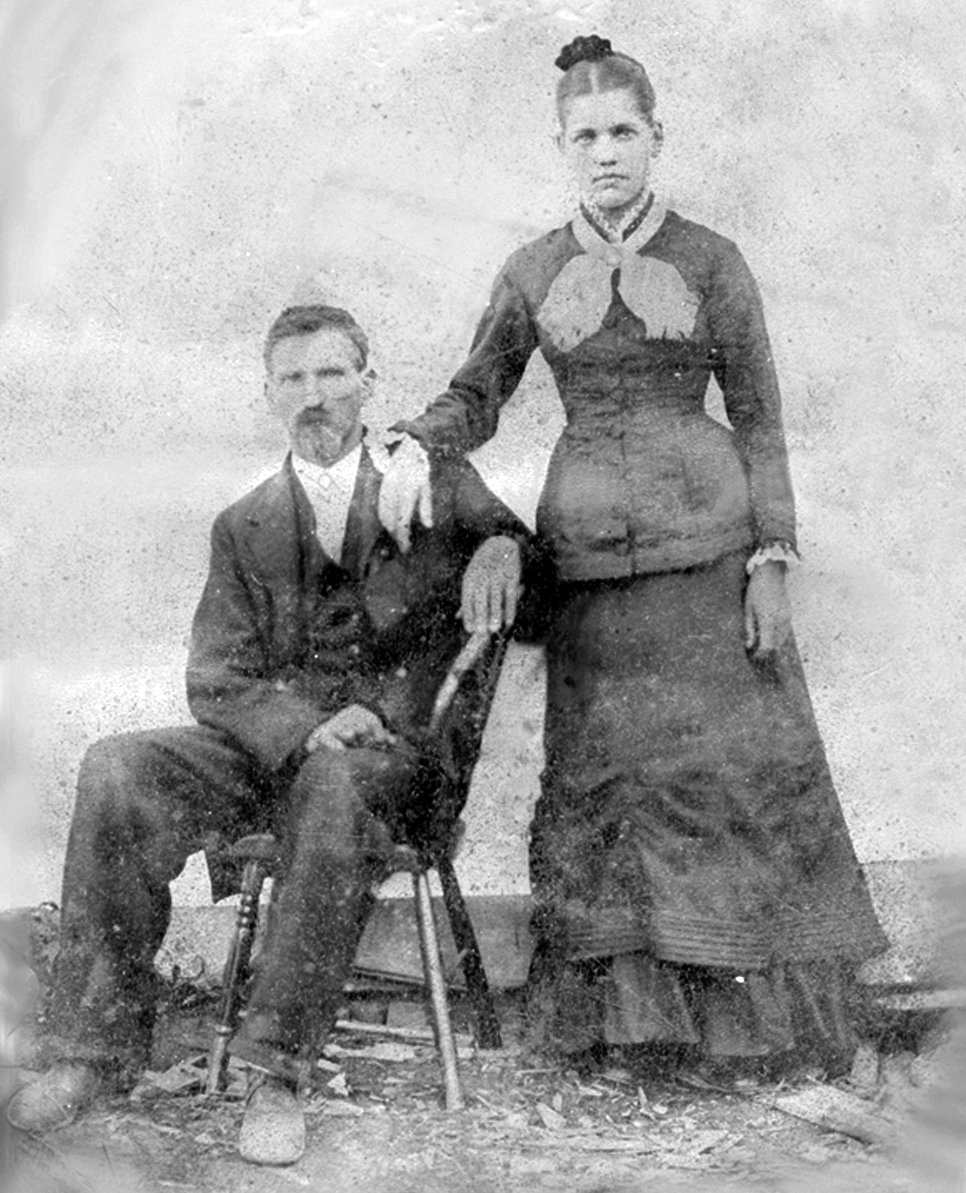

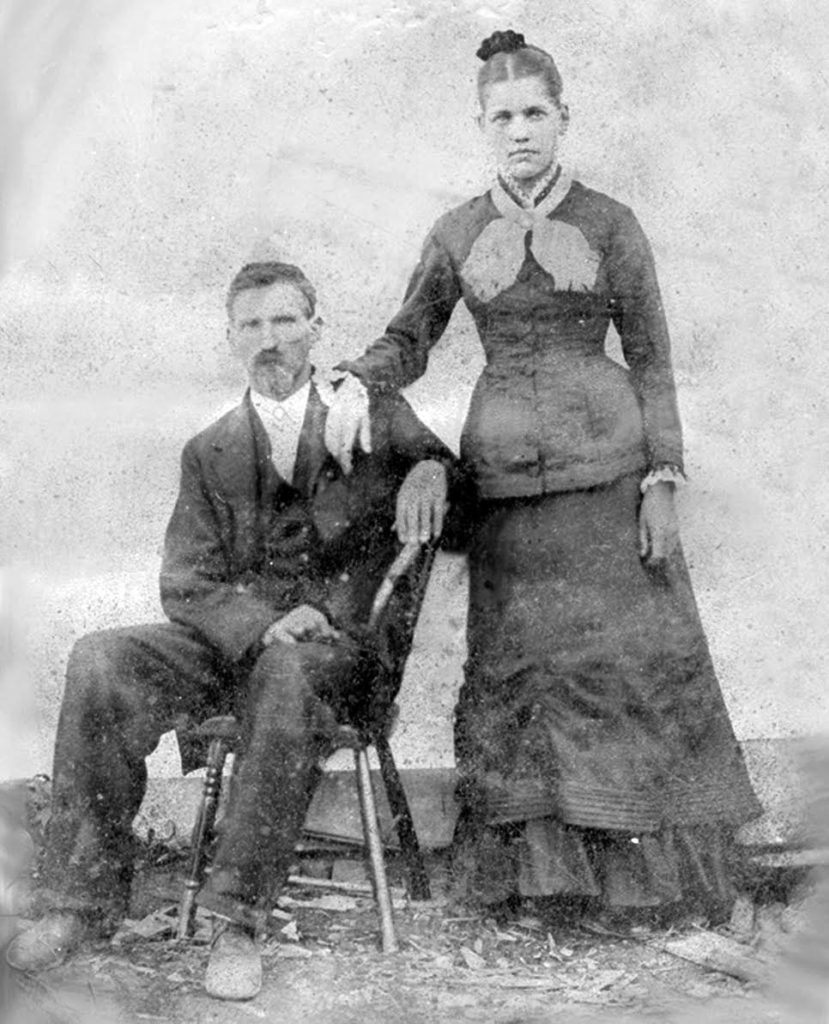

“Mom”, “Grandmam” – 1908-2011

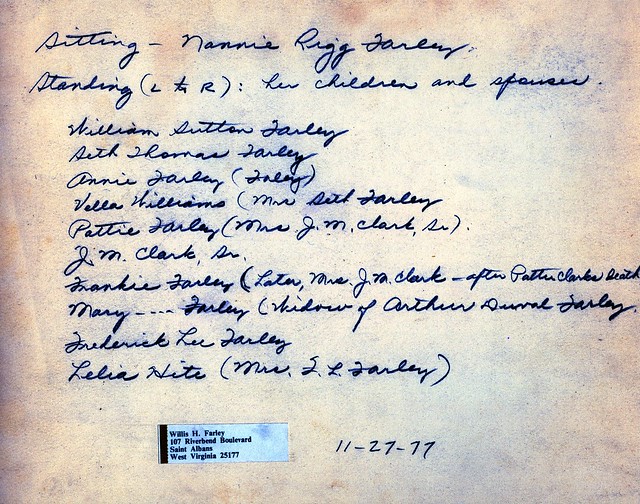

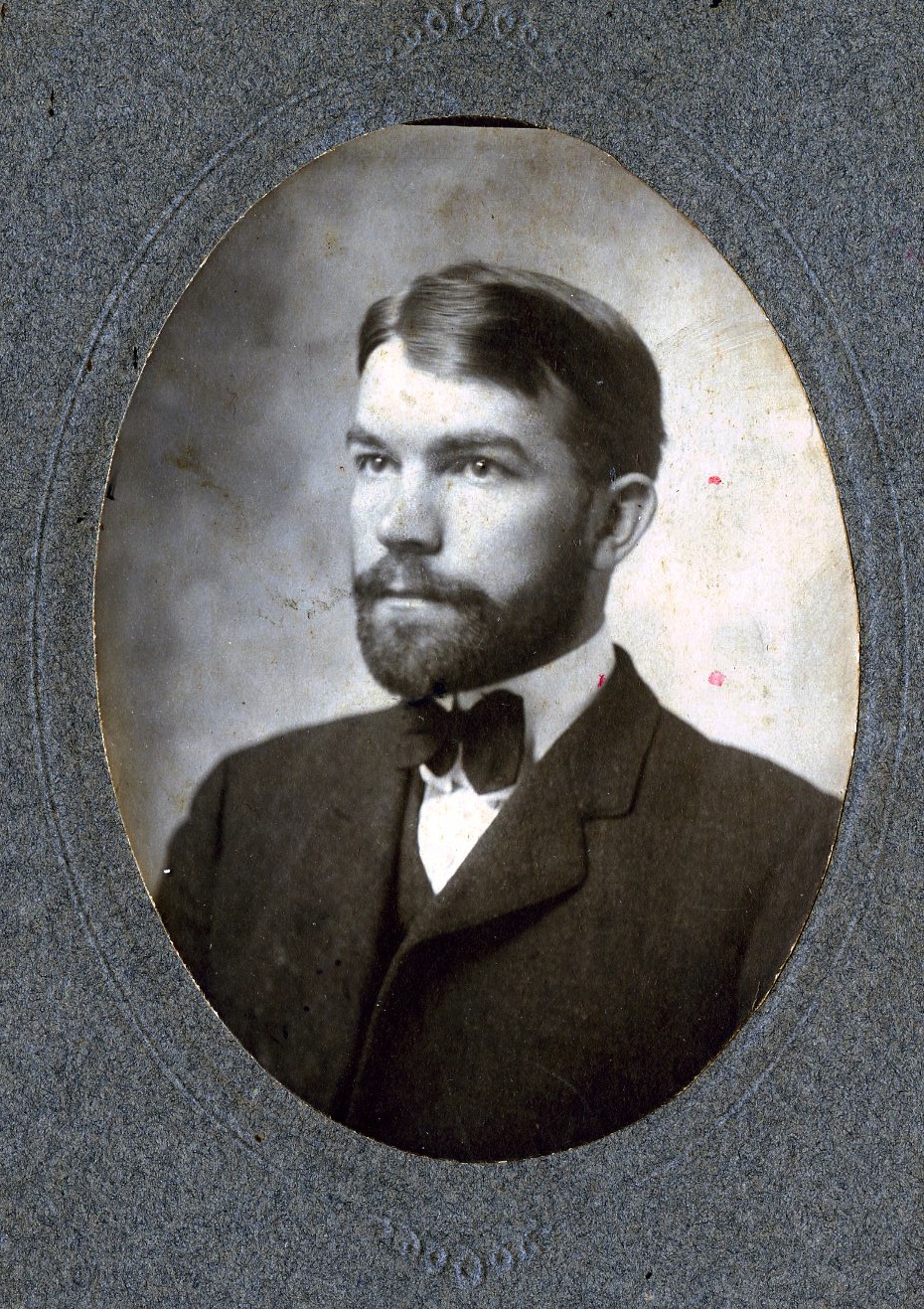

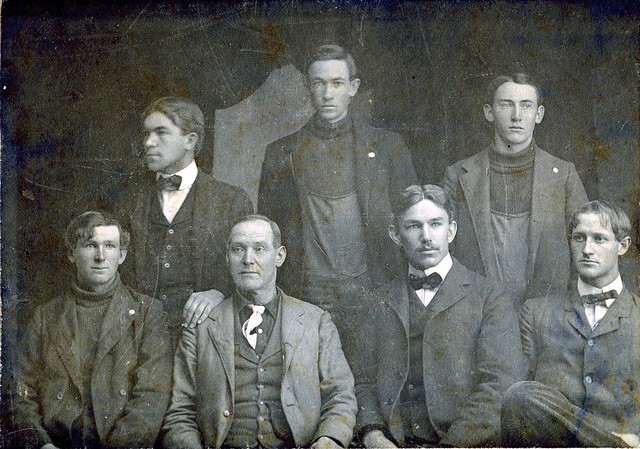

Audrey Farley was born in Cannel City, Kentucky on June 6, 1908, the daughter of Henry Orville Hale and Effie Rice Hale. She was the third of ten children. I don’t know much about her early life, except that she grew up in the coal mine communities of southern West Virginia, with a house full of brothers and sisters.

She (some of this can be found elsewhere in these pieces; I know I repeat myself, but this family stuff runs together at certain points) learned very early to work alongside her mother and sister Edith (Frances — “Rook” — was much younger) in the business of cooking, sewing, cleaning, working in the garden, and all the other tasks that befell the females of those times. At age eight, she was an able cook, helping with meals cooked on a wood stove, with no running water inside the house. Her mother was a task mistress who was too busy for nonsense among her children when it came to chores.

She was a fine student, and evidently had a couple of outstanding teachers in high school. At that small country high school Latin was required, along with great emphasis on literature and grammar. To the end of her life she could quote Shakespeare, poets and others whose works she was admonished to memorize. Her memory was prodigious. In her final years she could still quote poetry and prose without pause, and sing long, very old songs without missing a word or phrase. Her penchant for formal language belied her humble upbringing, and gave her an aura of unpretentious sophistication.

Truly, she had the heart of a scholar, although her life was anything but scholarly. Behind all that, she had a deep respect and admiration for the lifestyle of her parents, and never spoke ill of being a “coal miner’s daughter.”

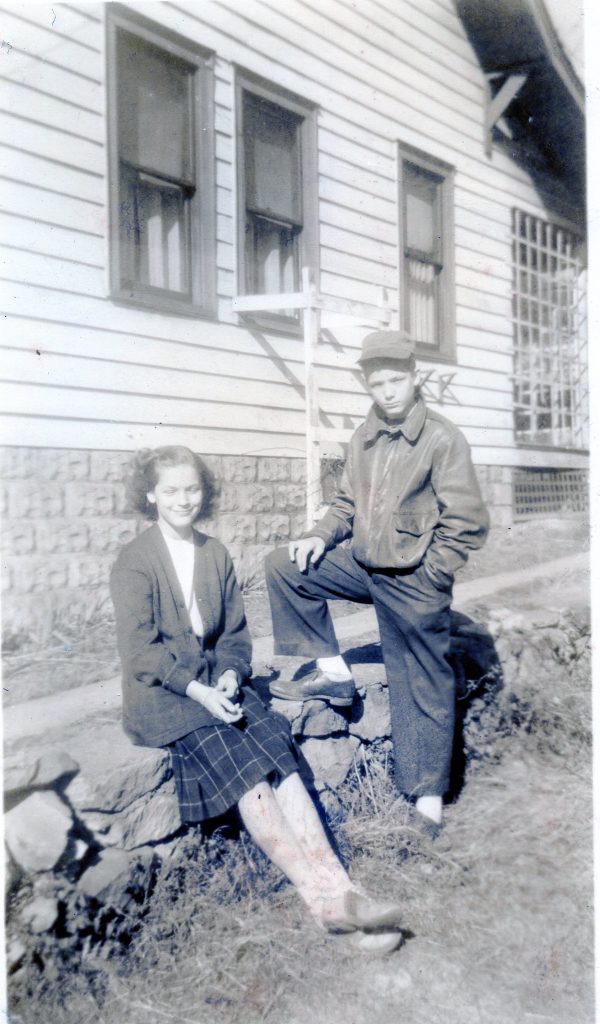

But don’t be fooled by this talk of scholarly talent. She was also known for her fiery disposition, competitive spirit and mischievous sense of humor. She knew how to have a good time, and among her school activities she played on the girls’ basketball team. Imagine: girls basketball in the 1920s! In a tiny high school in rural West Virginia.

And while she loved her poetry and literature, she never advertised it; rather, she presented herself for what she was: a person who understood basic values and a lifestyle that was unpretentious.

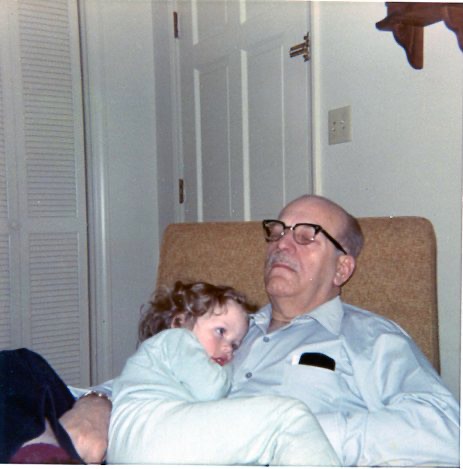

I cannot say enough about her innate ability as a mother. She was firm, kind, friendly, understanding, and most of all, trusting and encouraging. She had an amazing knack for knowing when and what to say or do to help a child be — a good child. Never heavy-handed or loud-spoken, she laid her intelligent, knowing, smiling qualities upon us all. Her three children were all different — nothing new there, but she never showed any favoritism; no one of us could complain or find fault with the way she handled the job of being a parent. I never heard her raise her voice or complain — I imagine she did, privately, but not in front of her children.

Times were not easy during the 1930s; the Great Depression had gripped us all, and many households were bogged down from the struggles of not enough money, too much debt, lack of optimism, and a dim view of the future. Mother wouldn’t have any of it. She kept the family going on that score, and Dad’s job at semi-skilled labor wages was nevertheless a huge positive factor in our family life.

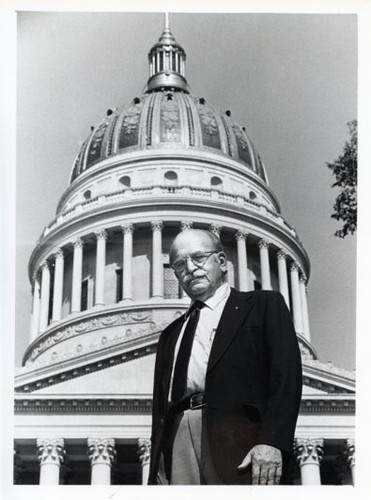

Like Dad and his and Mom’s parents, Mom was a diehard New Deal Democrat who was actually so biased politically — probably a result of the FDR years which saw an emergence from the Great Depression, and the unionization of the coal industry — that she had no use for any Republican politician, regardless of that person’s moderation or personal demeanor. In her later life, while watching a Republican on television, she would talk back at the TV with pointed remarks, all irreverent and many caustic, for the action on the screen. While one could criticize her single-mindedness in this regard, those moments were usually kind of amusing.

Mother and I had good times together. When I was in high school, we would wait for Wednesday’s delivery of the Saturday Evening Post, which included Western novels in serial form which we both liked to read. Often when I would get home from school she had cooked pinto beans, and we would test them together. When I was a pre-adolescent, we sang together — she taught me many songs (most of which I have long forgotten), usually while cleaning up the kitchen after supper.

It was mother who allowed me to go to the woods alone when I was very young. She needed only to know where I was going and when I planned to return. She never berated me for my missteps — I’m sure there were many — rather, she emphasized her quiet expectations of good behavior. Some summer mornings when I was eight or so I would arise at dawn, pull on my shorts and wander into the neighborhood, looking for anything of interest: birds, objects on our gravel street and sidewalk, you name it. When I’d go back to the house the world had awoken, and mother would simply say good morning, chat for a minute, and that was it. Can’t imagine that kind of freedom in today’s world; too many hazards for young kids. Looking back, those times were akin to the days of Huckleberry Finn, although my life was lacking that kind of adventure.

I note here that Dad’s working hours, which shifted from day to evening to night on a weekly rotation, placed limits on the amount of time he was at home during “regular” parenting time, so it fell to Mom to look after us kids, laying out the rules — such as they were — and by default acting as Parent In Chief.

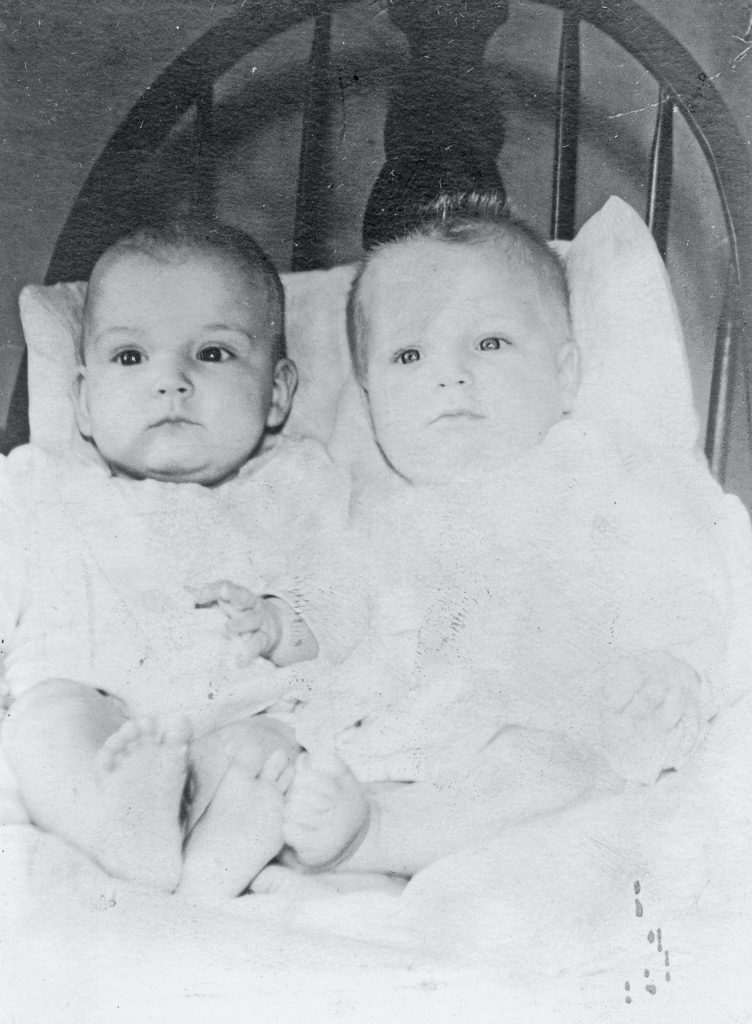

It’s important to say that mother’s parenting style was even-handed with all three of us kids. Dave and Alice were as encouraged and trusted as I. Mother was careful about that, but more importantly, she genuinely and effortlessly treated us all with the same expectations and affection; that’s just who she was.

Mom — that’s what I always called her; Alice was somehow more formal and never called her anything but Mother — was the model parent. I’ve had friends whose mothers were much like mine, and Carol’s mother was truly wonderful, so I don’t mean to paint her as the parent that no one else ever had. But she had a natural wisdom about how to deal with her children, and it worked. While Dad sometimes seemed a little hesitant about how to deal with us, as though he weren’t very self-assured about parenthood, Mom was never ill at ease with us — I think in large part due to her quiet self-confidence, as well as having grown up in a very large family where all the dynamics come into play sooner or later.

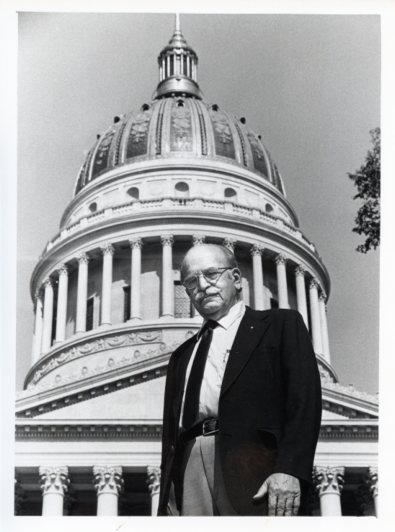

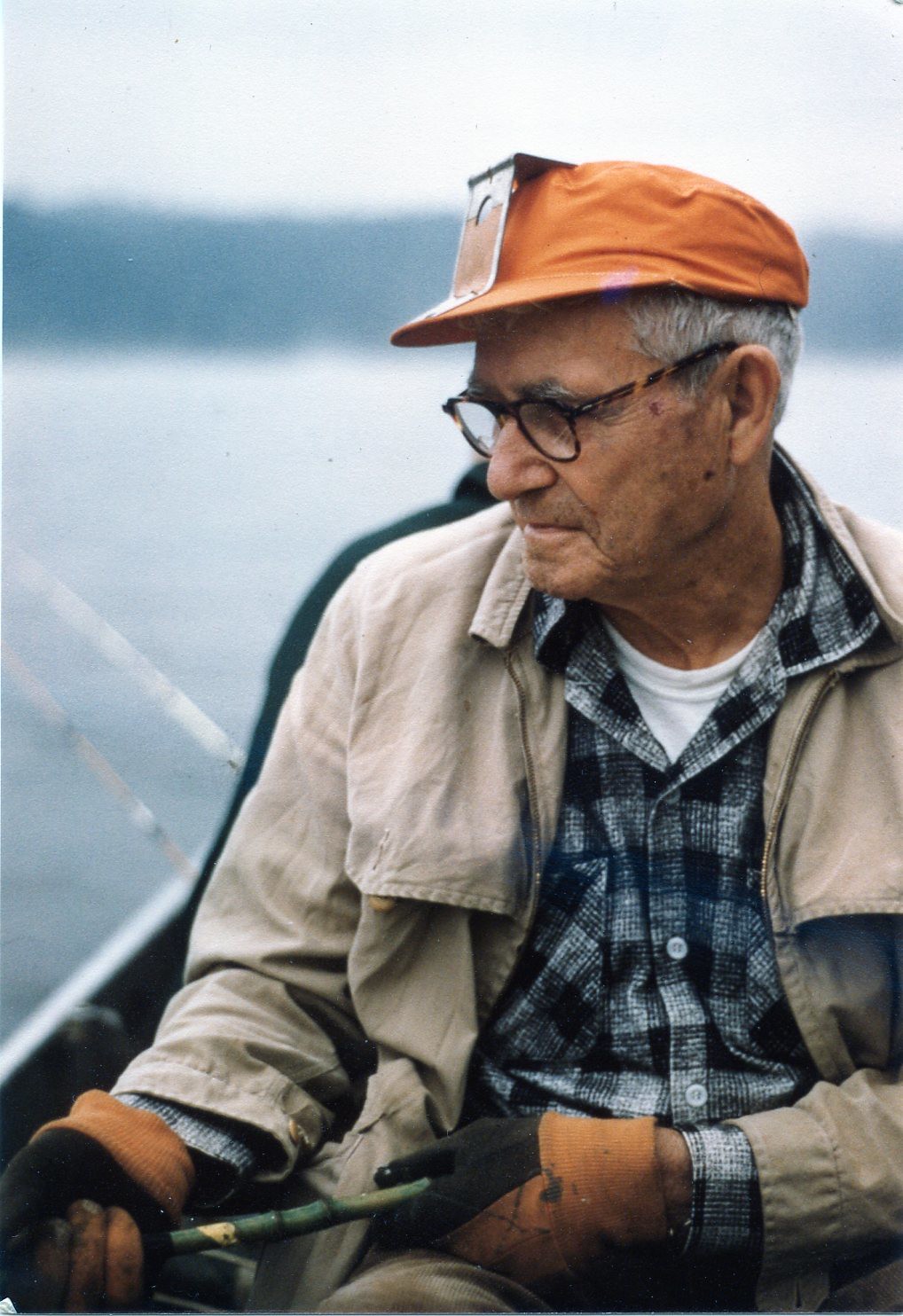

After we kids were grown and gone, she and Dad pursued their individual talents and interests; Dad with his politics and woodworking; mother with her love of nature and wonderful needlework. Her quilts were regionally known and shown at various events; several have been preserved by family members. (She made a quilt for Dave, Alice and me to celebrate our marriages, and individual quilts for her grandchildren. I hope you get to see them.)

Having grown up in “the country,” that is, in very rural surroundings, Mom learned from her parents a great deal about plants, wild flowers, birds, and nature itself. Not just her father; Nanny Hale was pure pioneer, and had learned the way of the mountains herself as a young child. Note in the family history her background and you’ll understand just how resourceful she had learned to be, using plants for seasonings, and so forth. So Mom had that 19th century background and simply carried it forward in her readings, her explorations of wooded areas close to home, and her conversations with others of similar background.

In 1961, she and Dad moved into their new home — the only home they ever owned — on the banks of Coal River, just outside St. Albans, WV. She immediately set out to create a wildflower area along the back of their lot, overlooking the river. The rich river soil, along with the shade provided by huge poplar trees along the bank, was a perfect setting for her project. It became a place of beauty which she showed to one and all with pleasure, walking along with a long stick with which she would point to the various flowers, naming them and adding a short note about their habitat, etc.

From her mom, (all the Hale girls called Effie “Mom”), Mother became an excellent cook; in later years she became an experimentalist, trying new recipes and seasonings, presenting visitors with exceptional dishes, learning all the while about how the kitchen could be a place of wondrous creativity. Her dishes were better than excellent — they were the talk of the neighborhood and church.

Dad died in 1983 at age 77, leaving Mom to fend for herself. She had never learned to drive, so neighborhood ladies from the church organized a group called “Audie’s Go-Go Girls,” who on a rotating basis took her to her medical appointments, the grocery store, and any other outings she required. That continued for 18 years, until her death in 2001.

Following Dad’s death, Mom became supremely independent, taking care of the house, handling the finances, and so forth. She was alone, and though she missed Dad terribly, she probably felt somehow liberated to follow her own path. She told me she really enjoyed living alone, with her books, her birds outside the kitchen window, and her tall poplars on the back lot. Her own path: those final 18 years were indeed lived as she wished — within the restrictions of her personal health, which was challenged by pulmonary limitations.

So Mom had reached her time of pleasure, after all those years of raising children, supporting dad, living frugally, directing all her energy and mental activity to the needs of the household — after all that she was able, at age 75, to unleash her creative notions into continued work with the needle, and in addition to learn how to paint, never forsaking her poetry and prose. Her quilts and wall hangings were just one facet of her artistic abilities: when she was in her eighties she began painting with water colors following a few lessons from a neighbor. Although she produced just a few paintings, they show true talent. Almost all of them portrayed flowers — quite natural when you think about it. Most of her paintings have been placed in the family “archives,” put together by Leslie as part of her tireless work with “ancestry.”

I cannot let pass mention of her love of reading. She had many favorite topics, and spent countless hours reading of current events and other timely topics. And for as far back as I can remember she loved western novels by the writers of the day: Ernest Haycox, Max Brand, Owen Wister and the rest. But her all-time favorite author was Louis L’Amour. In her final years she had a collection of about fifty of his books, and would read them over and over, more for the flavor of his writing than the content of the story. She often talked of him, and was taken by his descriptions of the west. One of her favorite comments was that no one could describe a campfire like Louis. We would take a dozen paperbacks to her at Christmas; she was always delighted. Her contacts with others were limited; she had little use for the telephone, and had few daytime visitors — probably her choice. Living alone in the evenings could have been tiring, but Mom was never quite alone…she had her Louis L’Amour books to keep her company.

Her light shone until her death in 2001 at age 93. Until her final day, she maintained her taste for pinto beans, good homemade bread, flavorful dishes, and yes, for her “turkey feathers,” a mere taste of Wild Turkey bourbon with a splash of water, taken on occasion before supper.

About everything in life, whether hardships, happy times, daily life: she had a prevailing sense of humor that parted the curtains time after time. That humor, characterized by her finding a source of smiles in almost any circumstance, was one of her trademark qualities: she could find a way to cast almost any condition in a positive light, and in my experience that quality is a rare human ability. And it explains in part her great parenting skill — bringing a child to feel okay about something when feeling bad was in the works. Positive reinforcement at its best. I know this sounds like an aggrandizement — even an exaggeration — of the life of one’s mother, coming from the pride of a child. But I am sure that others who knew her, family members or not, would agree with the memories expressed here. This was an exceptional woman.