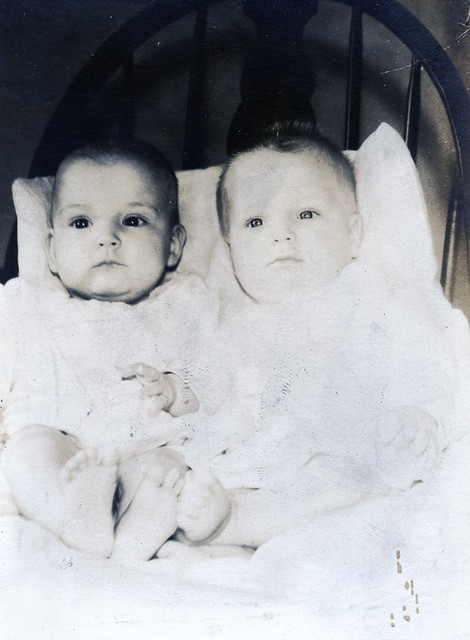

1931-2007

Alice and I, twins of course, were born in Winding Gulf, West Virginia on September 1, 1931. I’ve written about Alice in other pieces, and will take this space to tell you a little about her adult years. But before that, this:

We were what you’d expect from twins: played together, walked to school together, learned how to make up little games, all the activities of small children we did together. Then as we got a little older, we went the way of our genders: Alice with dolls, Alan with sticks and rocks and dirty paws. But we still were close. When were thirteen or so, she learned to smoke, as I had a year earlier. Cigarettes were precious during WWll, so our opportunities were limited. And smoking at that time was not considered a health hazard, even within the medical profession.

A dirty habit, yes, but that was it. However, it was a known fact in the family that I smoked, just not in front of adults. Alice, however, kept it a secret. Here’s a quick little story:

Our house on Sycamore Street had one bathroom, upstairs, a tiny room. Getting to the bathroom after supper with seven or eight of us was one of those unspoken contests, and Alice would finish supper early and race for the stairs. And go into the bathroom and light up a ciggie.

I would be close behind, but for legitimate reason. She would exit the bathroom and sail downstairs, I would go in and, upon leaving, would sometimes be met at the door by an adult. On more than one occasion, when I opened the door, Alice’s leftover smoke would as usual pour out. And I, who was far from innocent of many things, but had had not had a single puff, stood accused: “Alan Farley! Have you been smoking in the bathroom? Whew! Well, tell me, were you? You know you shouldn’t be smoking those nasty things anyway!” And on and on.

Each time I replied, guiltily, “Yes ma’am, sorry Mom, I won’t do it again.” Thus was Alice’s innocence preserved. And back downstairs, innocently, she would roll her eyes and silently giggle. And I would have to laugh, and she knew that. That scenario happened more than once. But that’s how it was with us; we’d cover as necessary, and it served both of us well.

We played in the band together, sang in the church choir together, hiked in Joplin Hollow together. When we were juniors in high school she was my date for the prom. (I had yet to begin dating girls, only stood with them in front of their lockers and watched them get on the yellow bus after school. I had only three or four “real” dates in high school.)

Alice had some great girlfriends, most of whom were, naturally, band members. They spent a lot of time together, doing girl stuff, while I was into camping, playing basketball, other guy stuff. The natural way of things had happened, each of us becoming more connected to other kids. But we were always known as a pair, and we continued to have those great private times together.

Although twins, there were many differences between us, both in physical features and personality traits. Alice was dark complexioned, I was fair. Alice eyes brown, mine blue. Alice was left handed, I, right. Alice was very private, I, sunny. Alice was nervous, I was oblivious. From our parents, Alice’s traits were somewhat more those of the Farleys, mine more — it seems — those of the Hales. And it may be that our differences played a role in how well we got along.

In my memory, we never had a serious disagreement.

On to the adult times. I’ve told you of our time together up through high school. Following those fun years, Alice went to WVU, where she majored in sociology. (I’ve mentioned elsewhere how she and I helped each other with college expenses: she helping me first, taking a job for two years; then it was my turn after I started my career and she was at WVU.)

During her senior year she and Robert (Bob) Bond, of Charleston and a student also, were married. Bob was in ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps), and upon graduation he and Alice moved to Cape Canaveral, Florida, where Bob — Lieutenant Bob — was stationed at Patrick Air Force base. Following his two-year stint in the Air Force, he took employment in the space industry with Martin Aircraft in Orlando, where he worked until his retirement. Bob is a great guy, was always a wonderful husband and dad, and had his own love of daredevil escapades with his Martin buddies. He was totally devoted to Alice, and they were a terrific pair.

Bob and Alice brought to the world three lovely daughters, Natalie, Margaret and Jennifer. Their ages were close enough to those of our three kids that they had wonderful times together, mostly at Christmas in West Virginia, and summer vacations in Florida. All of us — not just the kids — had great fun together, joking, sightseeing around Orlando, going for wild lake rides in Bob’s boat, and in West Virginia: watching the kids with their Christmas loot, helping in the kitchen, just . . . well, just being there together. (It is the three Bond girls who can best tell you of Alice, and it would be fortunate if they were to someday do so. My own information is, while not superficial, limited by the time and distance constraints which separated us during most of our adult lives.)

Alice was wife, homemaker, mother, community friend, flutist, best friend to her special buddies, and much more. She never stopped playing her flute in local orchestras and ensembles. She kept a high interest in state, national and world affairs, and was an avid reader with a broad range of interests. She devoted her energy and her life to her family, keeping the group going with good humor, often zany and always unpredictable. I’m sure her daughters can regale you with stories about growing up with Alice at the helm.

As for Alice and me, I can tell you that as twins we were truly bonded. From the time we had our own infant ‘language,’ at which we would go into uncontrollable laughter, until she died, we connected in silent ways not in the mainstream of personal relationships. We both felt we knew somehow when the other was in difficulty — or at least we both believed that. I can’t say with certainty that it happened, but I know that being together at (even before) birth, and living so closely during for our formative years, created an unusually strong bond between us.

Alice was as directed and determined as anyone I have ever known. Once she started on something, like playing a difficult symphonic passage on her flute, she was imperturbable and fully absorbed. In that respect we were very different. As noted earlier, she could practice the same passage over and over and over again, to the point of distraction for others, without once stopping for a breather or laying the flute down and later picking it up again. I remember too well that once, when she was about fifteen, practicing in her bedroom for an upcoming Charleston Symphony concert, part of the program was Beethoven’s Eroica Overture No. 3. In that piece there is a beautiful flute solo, not an easy piece for an as-yet amateur player. For about three weeks, she played that one passage over, and over. Every day for at least two hours. She wasn’t, of course, the orchestra’s first chair flutist, and the solo was to be played by the regular musician. But she loved it and was determined to master it. And she did. Trouble was, having mastered it, she STILL played it for two hours every day. Save me. That was Alice, throughout her life.

Her ability to focus was an important part of her lifestyle, and in her school life, success at scholarship — she mastered all her coursework, with her fine intelligence backed up by pure determination. But she never flaunted that skill, that scholarship; unless you knew of her abilities, you would not suspect their depth. While she developed a practiced art of appearing to be blasé, giving the impression that “well, it may matter not,” deep inside she was almost always alive with contained energy and attention to the matter that was before her. And that is the Alice we all knew: lively, friendly, caring, good-humored, with that wonderfully generous laugh, accepting.

I wish everyone could have a twin.