My first musical instrument was the flute. The flute had been bought for David, who four years earlier found more interesting things to do than blow across that mouthpiece. So when I reached fourth grade, it was determined that it was my turn with the flute — band lessons at school. Mr. Raspillaire, our band director at South Charleston High School, came to our school — Zogg O’Dell Elementary — weekly to teach our band class.

The above is a long introduction for a very quick ending. After three or four lessons, I told Mom that the flute was hard to hold up to my mouth with my right arm, and that I was not destined to be a flautist. So much for that. I was allowed to become a Raspillaire dropout.

Then, in fifth grade, we all got Tonettes — those plastic whistle-like instruments with holes to cover, changing the pitch — like a flute. Alice and I formed an immediate duet; we picked up on how to play songs, in harmony yet. Of course, by that time Alice had taken over the flute business, and continued to play for sixty years or so. More later on that. Anyway, we became the hottest act of our fifth grade, and showed our stuff at every chance.

About that same time, I had a sick spell and stayed home from school for about a week. Listening to local radio all day became a real bore, so one day Mom brought me a Marine Band Harmonica. I played my first tune, “Silent Night” I think, about two minutes later. Later on, I got a Honer Chromatica with the side button to play half steps. It was 1939; we had very little, so I don’t know where Mom found the money to pay for that “French Harp,” but somehow she did.

Then, one day Dad came home with a mandolin. Actually a banjo mandolin — strung and played like a mandolin with the body of a banjo — a round body with a skin top, with threaded screw-like tighteners all around the top edge. Dad had played a mandolin in his youth and someone gave him this one, so he was going to resume his own musical career. Sadly, I learned that Dad was no mandolinist, nor could he carry a tune or beat a rhythm. But I was proud of him anyway. The mandolin, of course, was donated to me, and I had real fun teaching myself how to use the pick across pairs of strings and play simple tunes. “Old Joe Clark” became my favorite. I never became a really good mandolin player; my young life was taking off in so many other directions — watching girls, all that, that music was merely a pleasant but brief part of my day.

Seventh grade: junior high school. Alice was having such fun with the flute, talking all the time about band practice, etc., that I got the bug again. So I went to Mr. Raspillaire and told him I was back for more, that I wanted to be in the band. I said the drums would be good. He started me with a pair of drumsticks and a practice pad, and I was ready to go. I carried my drumsticks with me all day at school, tapping on every desktop, railing, book — anything that had a flat surface. Then one day I was too energetic with the sticks and snapped the bead off one of them on the newel post at the bottom of the stairwell. You guessed it — I was a Raspillaire dropout for the second time.

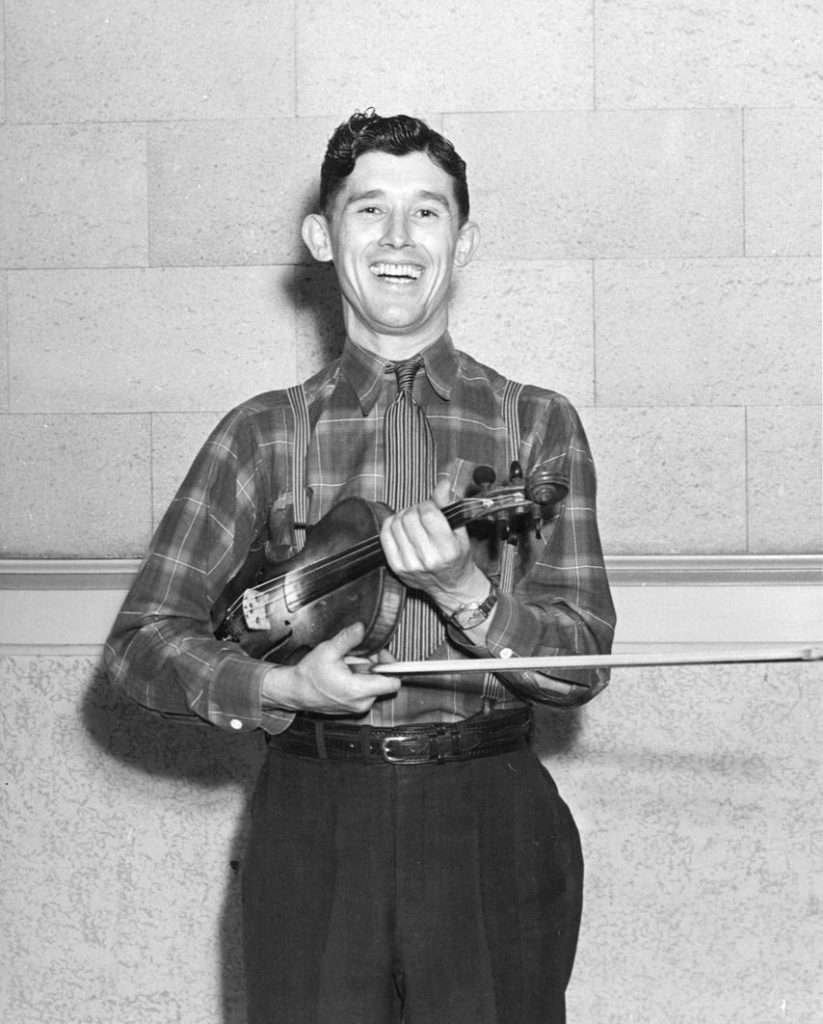

| Pete Raspillaire – Band Director, South Charleston High School |

By that time Alice and I filled the house with music every day — she with her flute, me with the harmonica and mandolin, and both of us singing silly duets. I knew I really liked music — I just hadn’t found my niche. Alice and I both joined the youth (“Young Peoples’”) choir at church, and David was teaching me to jitterbug in the living room — Les Brown’s “Leap Frog” was the song of choice, playing every few minutes on the radio.

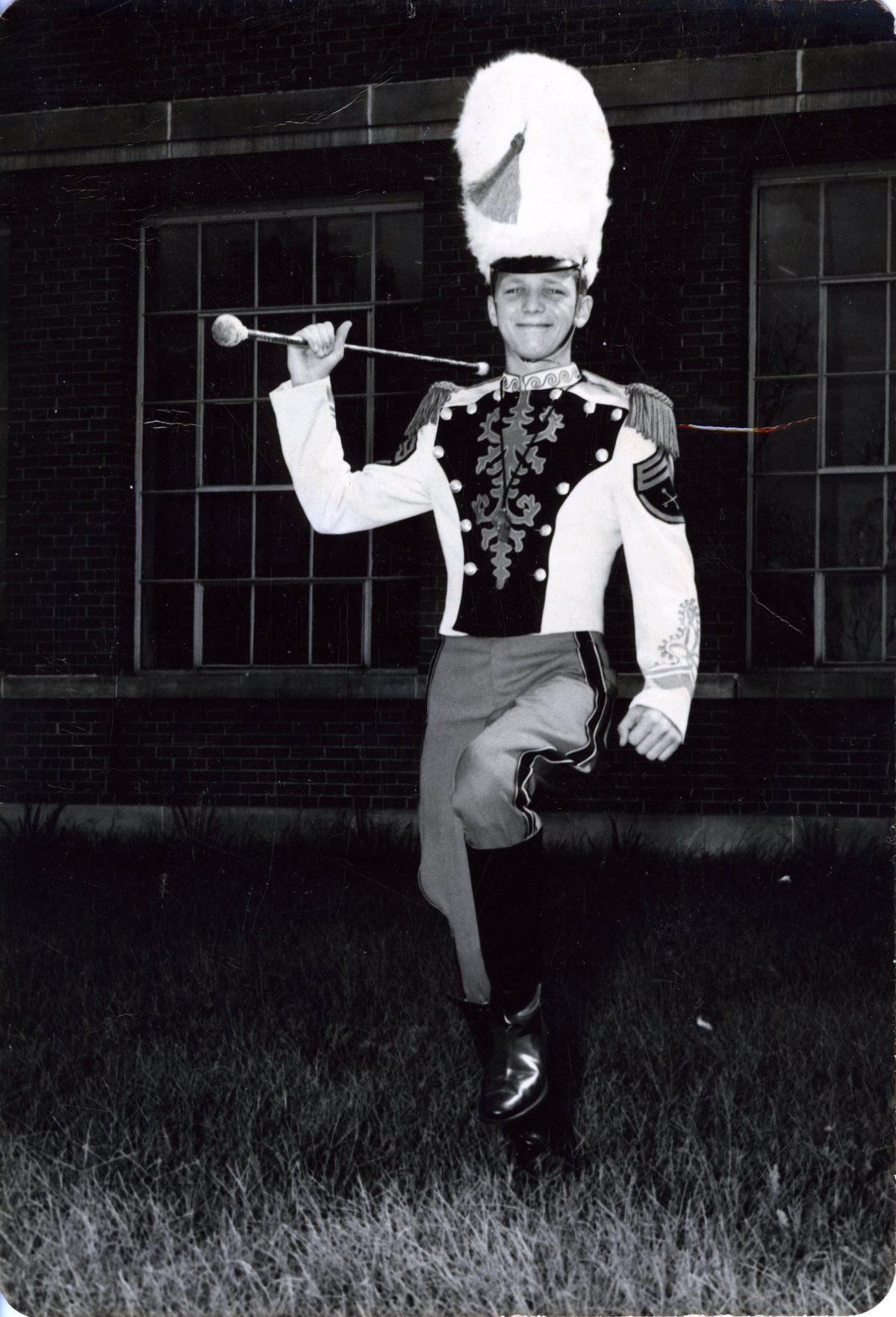

Ninth grade. That fall, Alice had her high school band uniform. Dazzling orange and black, with a leather shoulder strap. One Saturday she got dressed in the uniform early in the day. When I asked why so early, she airily mentioned that the band was going to an away game, on a school bus, no less. Then she added that the band traveled a good bit, and band members never had to buy a ticket to a game. I was intrigued. Go to a Black Eagles football game free? Ride the band bus to away games? What had I been missing! Of course, it was too late to join the band for the rest of football season, but in January, I went to “Pete” Raspillaire and told him I wanted to join the band. My motive, of course, was partly about the band bus, but I really did want to join for the music, having watched Alice’s progress for several years. I just don’t know why, but Mr. Raspillaire gave me yet a third chance! I do know that since Alice was a budding star, he perhaps had a soft spot for the Farley twins. In any case, he told me to see him after school that Friday.

So when I went to the band room on Friday, he presented me with a baritone sax that was school owned, and gave me a single sheet of paper with the C scale fingering diagram drawn in pencil. He said to take the sax home over the weekend and come back on Monday ready to show him what I could do. That was my big break. I took, or rather lugged the sax home, took it from the case and went to work. I soon found out that some of the keys didn’t totally close over their holes, there were loose springs, worn-out pads and the rest, but after several hours’ work it was playable. I looked at the C scale drawing, and, remembering the Tonette, I was in business. I fiddled around with the side keys, some Tonette fingering combinations, and the rest, and felt ready. I was so proud I even got Mom’s silver polish and cleaned the sax to a presentable shine. After working out the C scale, I actually learned a couple of others — probably F and G, along with three or four simple melodies.

When I played for Pete on Monday, he said OK, I was now a band member. Obviously, that changed my life forever, but that’s another story.

That spring, after four months in the band, I was selected to play baritone sax in the All-County Band. So I joined Alice and we were off.

My next instrument: cymbals. That fall, Pete understood that the baritone sax made no sense in a marching band, so he told me to play cymbals in the drum section. He gave me a quick lesson and I was up and running with yet another instrument. Of course, I couldn’t wait for concert season, when I would get back to the baritone sax. But that was not to be. You guessed it . . . my next instrument.

Oboe. A new student had moved to town, and she could really — really — play oboe. Her name was Jean Pike. In November, after football, I went to band class, got the sax out of its case, and we had our band rehearsal. As the bell rang Pete — I’m calling him by his nickname now because it’s so much easier than keying Raspillaire every time, and we all called him Pete behind his back — Pete told me to wait after class. I did, and to my surprise so did Jean Pike. Pete told me he’d like me to play oboe, but that I had a choice. Of course, the way he laid it out: every fine band has two oboe players, and so on. So I didn’t really have a choice. How could I turn Pete down after all the chances he had given me? So I said OK. Jean took me on as a student, and for the first time I had a true mentor who knew the instrument. I had never had a real lesson — even if you count the flute, the Tonette, the drumsticks, the harmonica, the mandolin, even the sax. I learned quickly — the fingering was so similar to that of the sax, and the double reed part came fairly easily. I was very, very proud to be named to the All-County Band that year, on a different instrument.

I finished high school as an oboist — neither Pete nor I had any ideas about new instruments.

By the way, when we were juniors, Pete asked Alice and me to play something in the Lions Club Minstrel Show, an annual fundraising event. Reluctantly, we agreed, not knowing just what to do. I told Alice I simply would not stand on stage with an oboe at a minstrel show. Bad match. So we got creative: flute and harmonica duet. We played “Waitin’ On the Robert E. Lee,” a ragtime-era train song, by popular request, and then we knocked ‘em out with “Temptation,” a sultry, Latin-type tune with lots of parallel major chords and chromatic runs. Lots of fun to drag those chords out of the Honer, with its chromatic button.

| Morris Harvey Swing Band; Alan is on far right of front row |

So, when I entered Morris Harvey College, I naturally signed up for band, chorus, music theory, etc. — all part of my curriculum as an announced business major. I guess my mind and heart were in two different places. The college owned a baritone sax, which I played. Then, because I was really into dance band and jazz, I talked Dad into signing off on the purchase of a new King Super 20 tenor sax. My rationale to Dad was that I could earn money for school by playing on weekends, which was true, and which I did. The tenor cost $180, and I was paid about $9.00, the then-Union scale, for a three-hour dance gig. So if you do the math you can see that the tenor paid for itself, and of course I made the monthly payments to Gorby’s Music for the purchase. Incidentally, I had to sell the tenor to my good friend Eddie Beulike two years later for $180 — enough to stay in school another semester.

A note here: when the college learned what I already knew; that I was a music major, the woodwind teacher found out about my oboe days in high school, and immediately announced that I was an oboe major. So be it, I thought. I finished my degree as an oboist, played my graduation recital, and went on to play occasionally with the Charleston Symphony Orchestra. But I also continued to play sax in local bands for ten or so years, until we moved from Charleston to Roanoke.

Back to 1950: My next instrument was my first guitar — bought at Gorby’s Music in South Charleston for $8.00. My excuse was that, with no piano at home, I could use the guitar to work out chords, etc. for my music theory class. The real reason? It’s no secret that I really loved country music along with all the other varieties, and the song Wildwood Flower, as performed by Maybelle Carter, had a fascinating guitar solo. I really bought that Stella so I could learn to play Wildwood Flower. Actually, the guitar did help — a little — with my theory class.

As is well-known today, in 2014, I bought a Martin guitar when I was 19. It stands in my front room as I write these memories, and it is in fine condition, ready to pass on to Leslie at any time now. Back then, I learned some bluegrass stuff like the Lester Flatt G Run, and I could do a weak mimic of Earl Scruggs’ style. So that guitar and I, along with Kenny and his ukulele, had some real fun. Leslie played an important role in the repair and rehabilitation of my Martin, and it’s the sweetest sounding, easiest playing guitar I’ve ever picked up. Leslie loves it, and it is hers. And the Martin knows Leslie; knows she can pick.

When I think about it, the oboe, the tenor sax, and the guitar were my all-time favorite instruments. The oboe and sax were around for just a few short years, while I’ve been picking the Martin for sixty-one years.

My next instrument wasn’t really mine . . . it was Leslie’s piano. We purchased a Yamaha piano for Leslie when she was about eight. She studied well, practiced well, and was basically well-taught by her (second) teacher. She took the piano with her when she moved to Charlotte, NC after college, and then traded it for a Yamaha Clavinova (electronic) piano, better known as a “keyboard.” That was in about 1987. Later, when she moved to Raleigh, she bought a very fine Yamaha Grand, and gave me the Clavinova, which stands beside the Martin guitar in the front room. I have always loved piano, and while I had no training whatever, I’m able to get around with a few chords and play favorite pop tunes, along with a couple of very fundamental works by Bach, Chopin and Beethoven. But the popular songs from my jazz/dance band days are my real favorites. I don’t play well enough for public performance, but as my own audience I am not displeased.

Finally, I suppose I should tell you of my most long-lasting musical instrument: my singing voice, for the voice is a musical instrument in the truest sense.

I think I began singing as soon as I could talk. As a young kid, Mom sang to and with me, teaching me songs from her own youth, as well as the best known western ballads, along with a smattering of pop tunes. As I mentioned earlier, Alice and I, being together all the time, sang together with progressively more advanced vocal abilities. We were in the youth choir at church together, and so on. Then, in high school I joined the chorus, and went on from there. I sang with a couple of my dance bands, and was in my college choir for four years. Along with all that, I sang, sang, sang to myself — all brands of pop, country and classical. And today, with my raspy voice, I sing, sing, sing. Aloud, but to myself.

I started as a soprano — ninth grade — and was a tenor in college (not by choice or voice quality; the director needed tenors more than baritones and I was elected), and today I am a true baritone. You probably wouldn’t think much of my singing — I’m actually an amateur at it. One semester of voice in college, and that’s it. But I know the basics very well — voice placement, breathing, diction, phrasing, projection, etc. etc. And you have read from my teaching days that I had really good high school groups, along with a really fine church choir.

So while my fingers grow stiff, and my facility with my hands fades, my last remaining musical instrument will probably be my voice. With its signature asthma-induced wheeziness, it’s mine and I’m keeping it.

Finally, while at Columbia I learned that — at Columbia at least — the conductor’s baton is considered a musical instrument. When I first head that I wondered “what’s going on here?” But as I had declared conducting as my chosen performance medium, it occurred that they were absolutely right; that the conductor is performing music with the baton.

Aside from incidental clarinet and alto sax work with dance bands, there you have it — the story of my musical instruments. They have their own stories too, but except for the Martin guitar and the keyboard they’re not around to tell those stories. I have to think — or certainly hope — they liked me as much as I liked them, for I took good care of them, they were played well and responded in kind — they fulfilled their life missions. I guess you know by now that music is my joy, my private and public fun time, a deep well of life memories. While I have had many, many exciting experiences in my profession as an educator, and while my interests include reading, writing, research, and the rest, it always — always — comes back to music. I’m talking, of course, about those motivations aside from family and friends, which are truly the essence of who we are. So if I’m remembered as the guy who couldn’t go through a day without a musical experience of some sort, that’ll please me greatly.