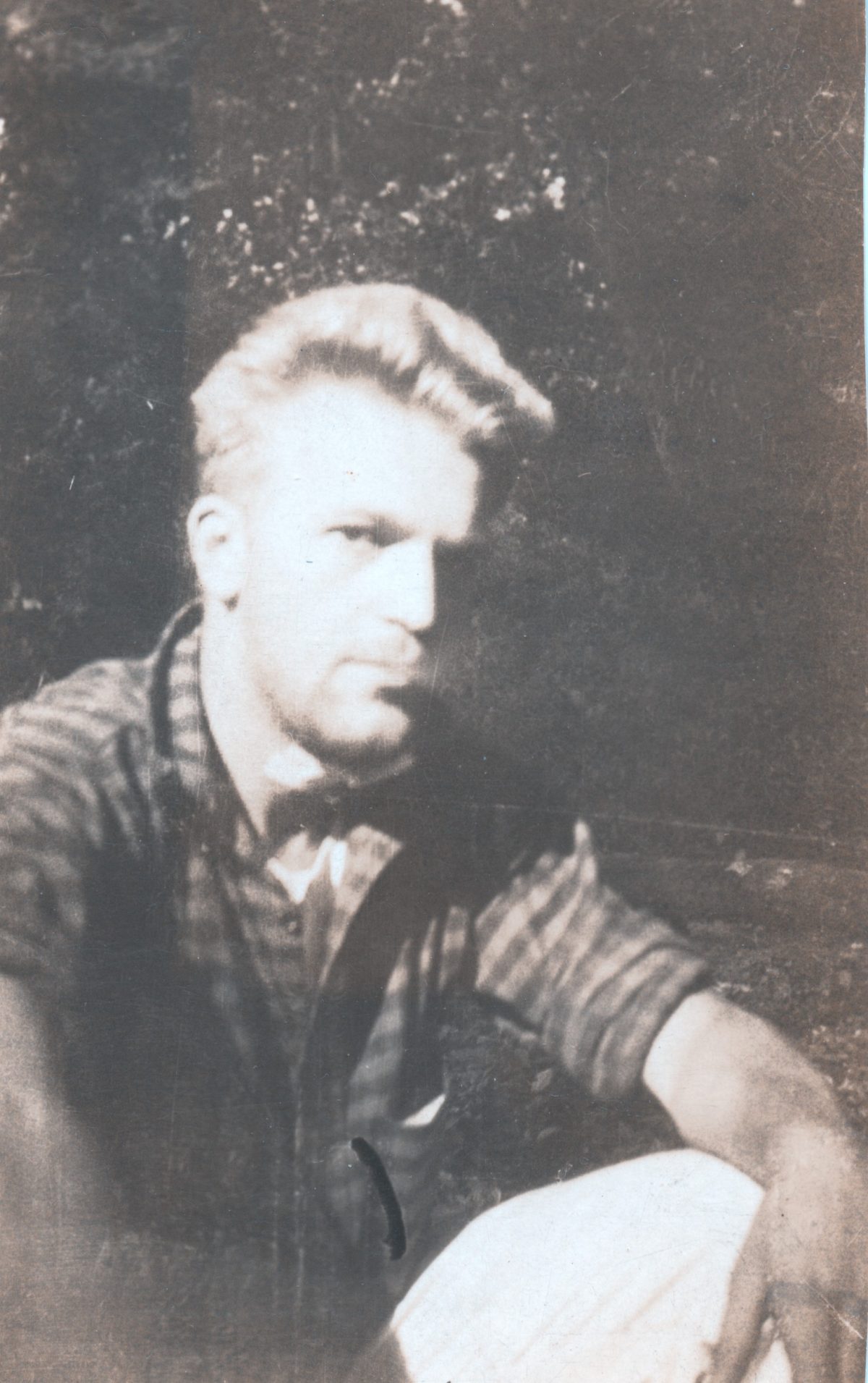

“Dad”, “Grandaddy”, “Big Bear” – 1906-1983

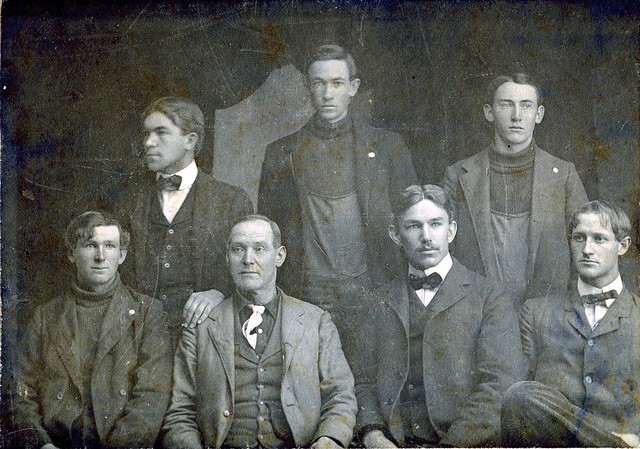

Willis was born at Kanawha Falls, West Virginia, a small town on the Kanawha River about 50 miles east of Charleston. He grew up in Alderson, West Virginia, another small town — with an estimated population of about 1,500 at that time — in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, on the banks of the Greenbrier River.

He was a willful young boy, and had friends who were likewise apt to go against the grain. They were boisterous youths, and had great fun in the Tom Sawyer tradition, pulling Halloween pranks and the like. During their early teens they spent their summers on an island above town, carrying their bare necessities up the railroad to the island and camping out. They would come and go from home, with parental permission (one must wonder if the parents didn’t applaud the arrangement). They would walk the tracks back home if needed, and walk back to the island, swiping chickens and corn on the way (Dad’s account). It was idyllic. They would bask in the sun, catch catfish, explore the nearby shores, play, fight, swim and the rest. What a life.

There’s an element of early twentieth century racism in this. Alderson was a really small town, decidedly white, and probably — no, surely, racist. I tell this because it’s part of the deal, like it or not. When Dad and his cronies went to “summer camp,” they convinced a black kid — their age — to go with them. He was to take care of camp, clean fish, help with cooking, etc. In return he could be a regular camper, eat with everyone else, enjoy the river, and the rest. Ingrained in the culture of the day, Dad and his buddies saw nothing wrong with this: a black kid would do chores and be rewarded with food and shelter, along with companionship in camp. While by today’s standards that would be unheard of, and truly in Dad’s later life is was so, it was just a reflection of life in those days for black and white alike in places like Alderson. Dad was careful to assure that their “colored” buddy was a true buddy, but that doesn’t clean the slate.

It’s instructive to state that by the 1960s Dad was the staunchest of civil rights advocates, and I’m sure he looked back on what were not innocent but unknowing days of the early Century with certain regret. Actually, he came by it as a matter of upbringing: his grandmother and mother were both of the racist mold of the day. I am heartened to say that Dad was an early proponent of equal rights; his basic human values prevailed, and he got it right — later on.

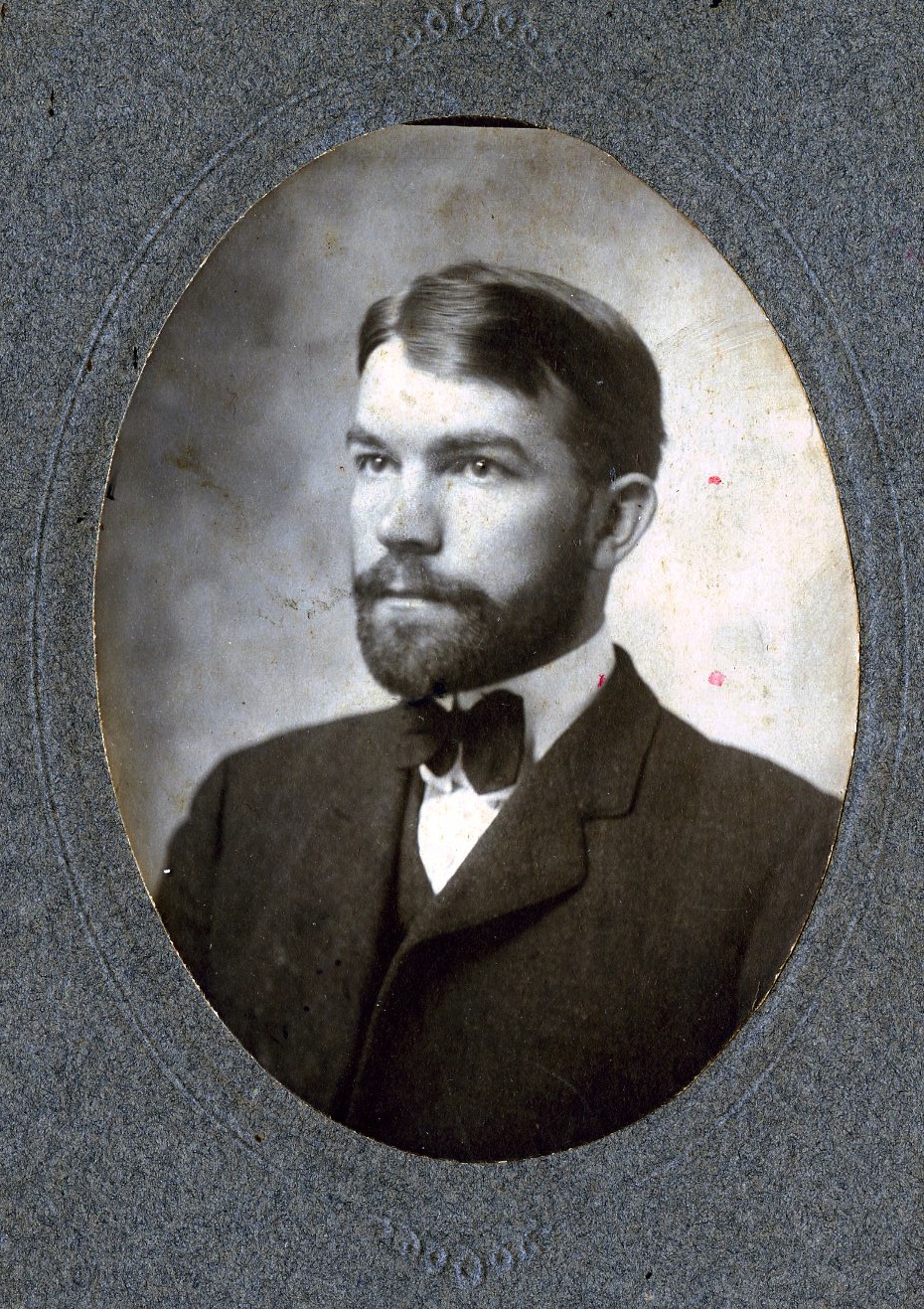

Dad had a hard time with and in school. After attending three different high schools — asked to leave the first two — he finally graduated. Upon leaving school he took a temporary job as an assistant to his uncle Seth Farley, who was a surveyor for coal companies in Greenbrier and Raleigh Counties. He was enthralled with the experience, and never got over what he called “the romance of the mines.”

A little later, he met a young girl with a zest for living and an adventurous spirit. She was Audrey Hale, who became his wife and my mother. They were young and improbably optimistic. They moved to a small mountainside coal camp called Quinwood, in Greenbrier County. The company houses were literally built on stilts on their fronts, with the backs anchored to the steep mountainside.

Dad didn’t even work in the mines — at that time. He worked in the company-operated pool hall, racking balls and serving food. But he reveled in being a part of the coal mining way of life, a dream that later became a reality, and finally a lifelong fixation.

It’s hard to imagine a person being that taken by a life underground, with pick and shovel as it was in those days, with the carbide lamps and the canaries and the rest. But I have known miners from those times who were just like dad. As the great song “Dark As A Dungeon” says: “It will form as a habit, and seep in your soul, ‘Till the stream of your blood runs as black as the coal.”

A little later Dad and Mom moved to Raleigh County, where Dad took a mining job at Winding Gulf, which at the time was one of the largest mining operations in the area. There, they became the parents of my older brother David in 1927. Life in coal camps was tough then — work with little else to do; near-squalid home conditions, no access to the outside world, just work, coal dust, and worry. The company owned the homes, and paid their employees in “scrip,” which was in the form of tokens to be redeemable at the company store. To exchange one’s scrip for cash meant selling it at discount, so employees were stuck with buying everything — food, clothes — everything, at the company store. As the great song goes, “You load sixteen tons, and what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt. St. Peter don’t call me ‘cause I can’t go — I owe my soul to the Company Store.”

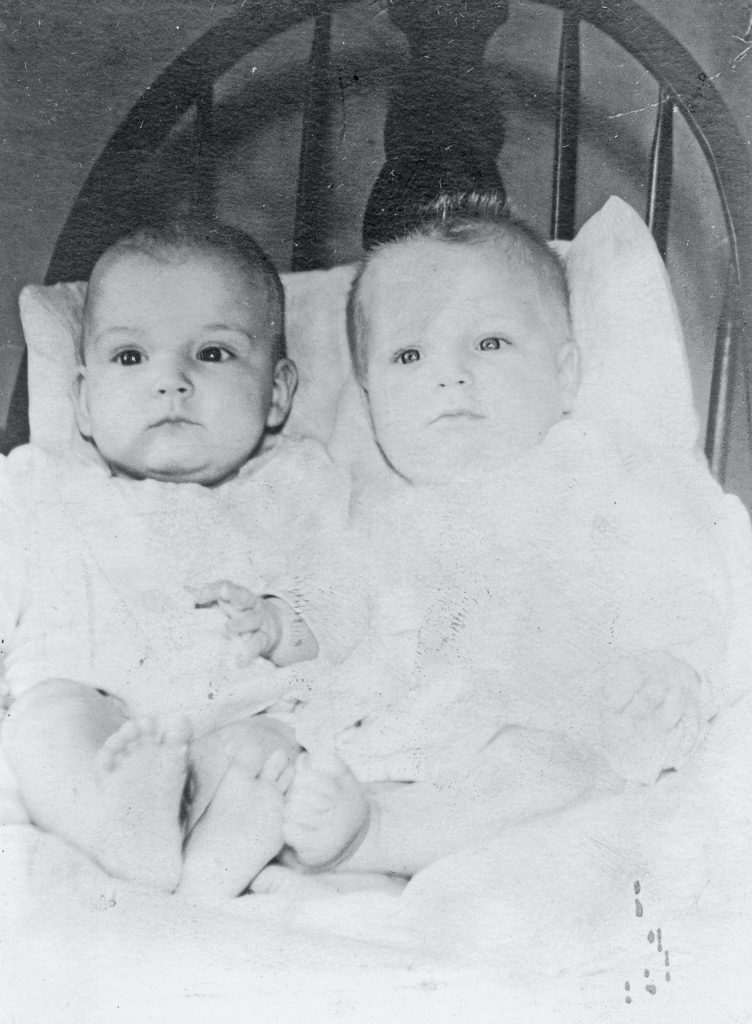

Then came the twins — Alice and me, in 1931. We were a surprise. They expected one newborn and got two. I’ll not repeat here what I’ve written in “Earliest Memories,” which speaks to my early memories of life in Winding Gulf. Instead, I’ll pick up with Dad as life progressed in South Charleston, when I was a youngster.

Dad loved to talk politics, even in those days. A fervent Democrat, he spent dinnertime adulating President Roosevelt. No wonder — life in the Great Depression years was a time of hope for the working class, and Dad was a union man through and through, having cut his labor teeth on John L. Lewis and the United Mine Workers. We would come to the supper table, eat and sigh as Dad preached the union gospel. Not that it was bad. It was just not what young kids were about.

Among the tales of Dad’s political “events,” including a failed candidacy for the state legislature, this one took the cake: Harry Truman was President, and had scheduled a vacation in Georgia. This was during the time of the southern rebellion against the Democratic party, spearheaded by the infamous Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who broke away from the party and ran for president as an independent in 1948, sparking Truman’s famous characterization of “Dixiecrats.”

Knowing of the planned getaway, Dad’s imagination took off. He got Mom to make a short-sleeved sport shirt of fabric with a Confederate — a la “Dixiecrat” — design. In fact, he had her make two of them. He sent a shirt, along with a tongue-in-cheek letter, to President Truman at the Georgia retreat.

Behold! Dad received a personal letter from the President, also tongue- in-cheek, thanking him for his thoughtfulness. I was living at home at the time, and the whole event was hilarious — and Dad was ecstatic. He harrumphed around the house for days — hard to tell what he said to the guys at the plant.

And as to talking, Dad would take the opposite view of any topic or position just to stir a debate. Mother told me that when they were first married he would say, name a topic and take either position; I’ll argue the other side. And that quirk in his nature was deeply embedded; it remained part of him throughout his life. Many times I would state my support for what I knew to be his bias, just to get him to fend for the opposite view. Great entertainment. He just loved verbal battle.

Willis Farley believed in strict organization. I won’t give it any big psychological slant; I’ll just say what he was. He was OCD about his tool cabinet. Mislay his hammer and you were in serious trouble. He was also a minimalist about a lot of things. If you could use something twice before discarding it, that was the thing. And so on. Of course, a lot of that was due to being without for so long, and a fear — nay, a terror, that being without was just around the corner again. Rather than being upset about it, we kids took it all in stride, and had no issue with Dad’s way of doing things. We just weren’t ecstatic about his manner, his basic pessimism.

He was a loyal Freemason. Almost to the point of obsession. He eventually became a thirty-third degree Mason (whatever that is), and an avid Scottish Righter. His spare time was spent reading Lodge magazines and coaching young aspirants in the early degree regimen of the Lodge. I never paid much attention to it, nor did I ever have an interest in joining. But Dad — now Dad was another story. He gained a reputation locally for being the best coach in the Lodge, and I’m sure he was.

He was a fine wood worker — although he never built a piece of furniture, he became highly skilled at restoring old pieces, and was a true craftsman. After the kids were grown and gone, he and Mom would go to farm auctions and buy old pieces for a song, with Dad scraping the undersides and discovering the kind of wood, the condition of it, and whether it was really valuable. He and mother had a great time going to those auctions, picking up old but valuable antique furniture and working together to bring it back to its original beauty.

He was a caring parent. While there wasn’t a lot of communication, he was interested in our futures, and was willing to talk with us about most anything. He wanted us to succeed where he hadn’t, and was proud of our achievements. That he had a limited sense of humor was no problem for us — we learned early to expect that.

That he sometimes had a temper was just who he was, and we knew it would pass.

He was always concerned about providing for his family, and as a “working man,” sometimes felt that what he brought home in his weekly paycheck wasn’t enough. But it was. There was little to spare, but enough to get along.

He loved to camp and fish. That from his boyhood on the Greenbrier River. I camped with him many times, and he loved to tinker with his gear, fuss with the tent, fix a special place to put the wash pan, and so on. He couldn’t cook worth a damn. His only dish was “shantyboat stew,” an overcooked mix of soup, cut up meat and potatoes.

But he was a meticulous camper, taking care of gear and keeping a neat tent, cot and kitchen. And eat fish! Man, he loved fish. He would eat every morsel on the platter and look for more. Especially catfish — channel cat. He showed me how to nail the fish to tree and skin it with pliers — a time-honored practice in the southern mountains.

He was an avid environmentalist. Early in the national awakening of environmental consciousness, he became very active in the “movement.” His interest dated back to the 1950s, when he noticed that Union Carbide was dumping chemicals into the Kanawha River late at night, when no one would be aware of their actions. He went to plant management and called their hand on it, threatening to ‘blow the whistle’ if they continued. For a while, at least, they stopped the practice. From there it was continued activism regarding clean water and air. On one occasion he provided testimony for a congressional committee. He was one of a small group who successfully stopped the construction of a dam on New River in Virginia/North Carolina which would have devastated thousands of acres of farmland and disrupted one of America’s natural treasures.

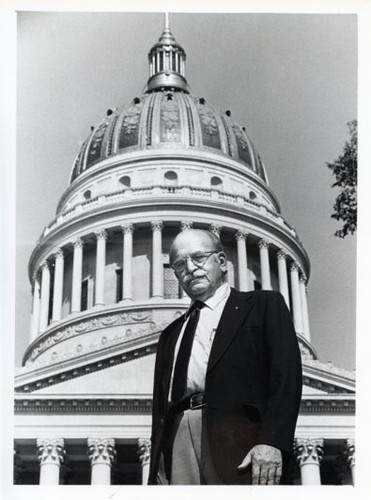

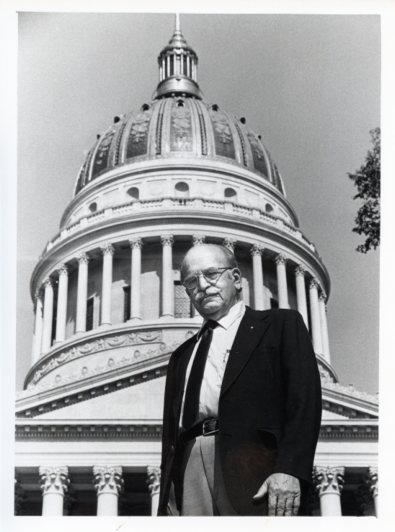

In retirement he would stalk the halls of the state capitol, lurking around corners to buttonhole legislators to lobby for environmental issues. His dedication to the environment was not lost on the people of West Virginia.

In recognition of his advocacy for clean government and a clean environment, he was named President of the first Silver Haired Legislature in West Virginia — an honorary title well deserved. So even today, hats off to Willis Farley — a man ahead of his time when it came to environmental activism.

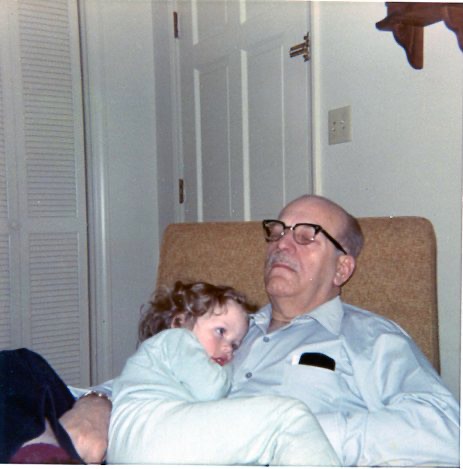

Above all, he was a great grandparent. When his grandchildren started coming along he was a changed man. Rather than the stiff, silent, argumentative Dad I had known, he became the guy who rolled on the floor with an infant, talking baby talk, the whole deal.

And as the grandchildren grew, so he grew in his affection for them. He was always gentle and giving, and went to great lengths to make their lives happy.

Not quite the Dad I knew, but certainly the Dad I admired for being so good to my kids. It came to me that that was the Dad he had always been, he just didn’t know how to pull it off with us because of the burdens of parenthood: debt, family obligations, worries about family, uncertainty about the future, and the rest. I can’t possibly say enough about how good he was to my kids — he genuinely loved being a granddad, and he genuinely loved his grandchildren. Whatever his other shortcomings, they were overshadowed by his being “Big Bear,” the great grandparent. He was a really good man, a good father, and a good husband. His faults were neither greater nor less than those of other good men. And his contributions to making life better — and safer — for others, while mostly unsung, were indeed remarkable.