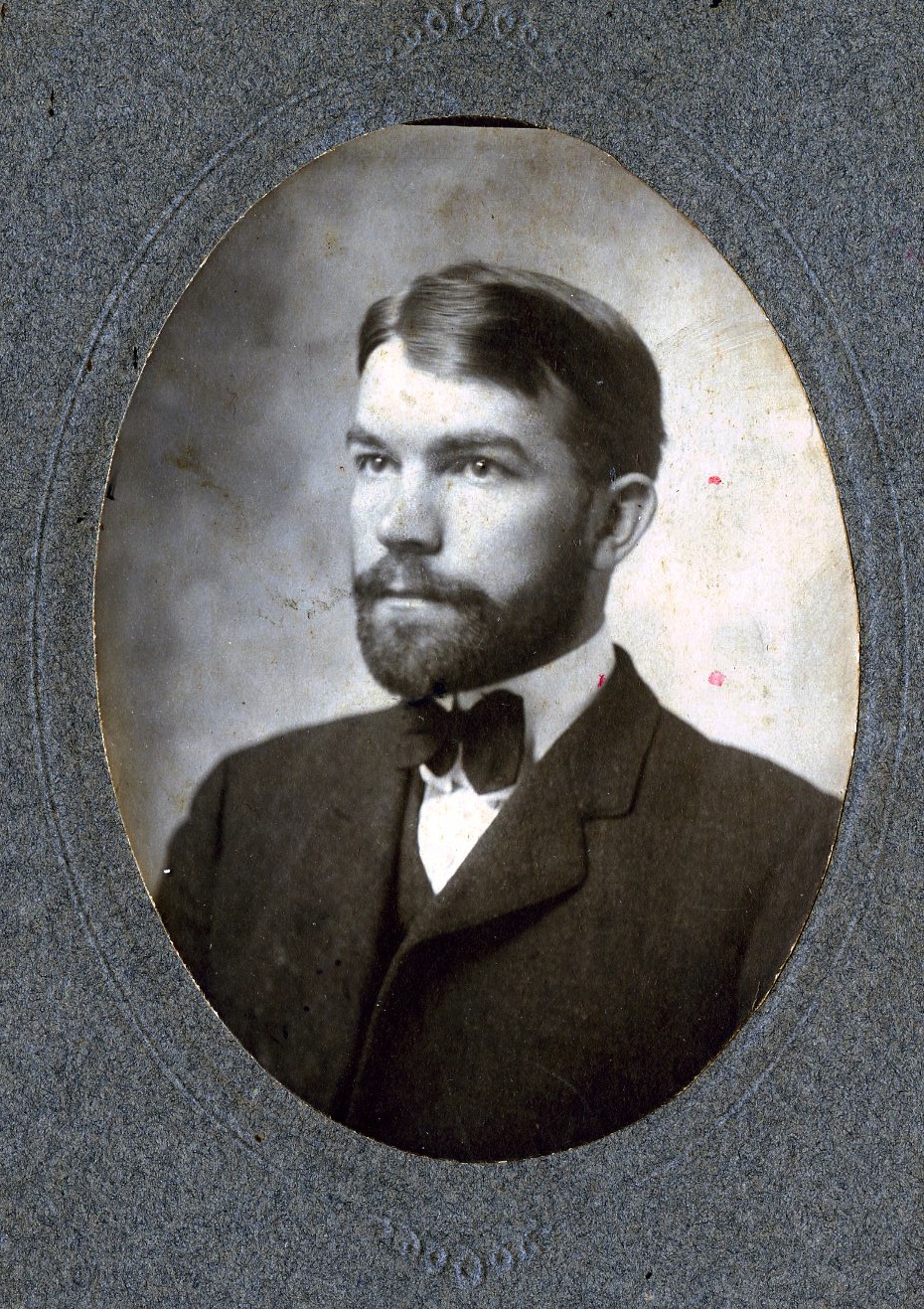

“Granddad Farley” – 1879-1945

Fred Farley (my paternal grandfather) born in 1879 and died in 1945, was a well-spoken man who grew up around Kanawha Falls, West Virginia. He was a friendly, outgoing man who loved a good laugh, loved to play a card game called Setback, and loved to tease his young grandchildren. Everyone loved Fred Farley. Much of his working life was spent in West Virginia’s quarries and mines, and for several years he was a mine inspector for the State of West Virginia.

His final job was as superintendent of a limestone quarry in Daily, West Virginia, which was a town supported by the Homestead Act and promoted by Eleanor Roosevelt. Fred was — no surprise here — a hot Democrat who had an Irish temperament about all things politic. I remember him as he sat by his radio during the 1940 Presidential campaign, hooting at the Republicans and applauding Franklin Roosevelt.

Granddad was also a prize fight fan. Again, I sat with him beside his tabletop radio when Billy Conn, whose Irish name endeared him to Granddad, challenged the heavyweight champ, Joe Louis — the “Brown Bomber.” When Louis won that famous bout, Granddad was beside himself. He had hoped for a victory for a tough a Irish kid from Pittsburg who had been the middle weight champ and decided to take on the unbeatable Louis.

Granddad Farley was generous, outgoing, and optimistic in spite of his family life, which was under the heavy influence of his mother-in-law Alice Hite, and wife Lelia, who in many ways tread in her mother’s footsteps. Despite the cloudiness of his home life, Fred was always cheerful and giving. He loved a good joke, smoked one cigarette off the end of another, went into brief tantrums when the card game didn’t go his way. As young kids Alice and I were always delighted by his presence. We always thought of him as the rather short, rotund Irish-looking man who would have loved being Santa Claus.

By all accounts — both from his children and especially as told to me by my mother, he was a really good father. His youngest child, my aunt Ruth, told me this tale:

Ruth was about 14. She had a girlfriend who lived behind her, and they would sneak behind the friend’s barn and smoke cigarettes swiped from their fathers. (Remember, this was in the 1930s!) One day, she and her friend decided to skip school and hitchhike to White Sulphur Springs, a nearby town. (It’s hard even for me to imagine two young girls hitchhiking on rural roads in that time.) They had a fine day of it, and as they hitchhiked home a car pulled up and to Ruth’s horror, it was her father! He simply opened the door, the girls got in and he pulled away. The girls were terrified all the way home — about ten miles.

Ruth told me that her father never said a word. When they got home, they simply went into the house as though nothing was out of place. To this day — Ruth is about 90 now — she has never forgotten the lesson of that day. By saying nothing, her father couldn’t have given her a more telling message: that he disapproved of her actions, that it wouldn’t happen again, and that his love for her was not damaged. When Ruth told me that tale a few years ago, I thought to myself that that was true, vintage Fred Farley: don’t overreact, and give your kids a chance to think through their own behaviors.

Granddad Farley was in many ways our favorite relative. We were always delighted to see him — in those days of the Great Depression we would see our grandparents no more than twice a year — and he was likewise the favorite of his adult kinfolk. When Alice and I spent summers with the Farley grandparents, it was Granddad who made our young lives happy. He took us to the drug store for ice cream, bought us scooters, played kids’ card games with us. I think he gave extra effort to us to make up for the coolness of Nanny and Mammaw. Young people always love to be recognized, listened to, treated as equals. Granddad Farley intuitively knew that, and lived it. Much later, I came to admire my Grandfather Hale equally, and for a lot of the same reasons. More later about that.